🌀When Chaos Becomes the Solution

What Dancing Particles Teach Us About Hidden Order

Gold particles dance—

chaos filters coherence,

spin pattern emerges

With every article and podcast episode, we provide comprehensive study materials: References, Executive Summary, Briefing Document, Quiz, Essay Questions, Glossary, Timeline, Cast, FAQ, Table of Contents, Index, Polls, 3k Image, Fact Check, Comic and

Street Art at the very bottom of the page.

Soundbite

Essay

There’s a particular kind of arrogance in how we approach disorder. We see chaos and immediately assume it’s something to be eliminated, controlled, or at the very least, apologized for. Our entire technological civilization rests on this premise: randomness is the enemy, order must be imposed, and cleanliness—whether in data, processes, or physical systems—sits next to godliness.

But what if we’ve been getting it backwards?

A recent discovery in optical physics suggests that sometimes, the mess isn’t just acceptable—it’s essential. It’s not merely that we can work around disorder; it’s that disorder itself can become the most elegant solution to problems that perfect order cannot solve.

The discovery is called the Brownian Spin-Locking Effect, and it emerged from a collaboration between researchers at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Technion in Israel, and Tongji University in China. On its surface, it’s a story about light and nanoparticles. But dig deeper, and it becomes something more profound: a meditation on how we understand randomness, control, and the unexpected places where truth reveals itself.

The Setup: A Perfect Paradox

Imagine a container of water filled with gold nanoparticles, each one tiny enough that you’d need an electron microscope to see it. These particles aren’t sitting still. They’re being constantly bombarded by water molecules in perpetual thermal motion—what physicists call Brownian motion, named after the botanist Robert Brown who first observed pollen grains jittering under a microscope in 1827.

This jittering is pure chaos. Each particle follows an utterly unpredictable path, knocked this way and that by molecular collisions happening trillions of times per second. If you wanted to design a system to destroy delicate physical effects, this would be it. It’s like trying to read a book while riding a mechanical bull during an earthquake.

Now shine a laser through this chaotic soup. The light has a property called spin angular momentum—essentially, it rotates as it travels. Every optics physicist’s training would tell them that this delicate rotational property should be scrambled beyond recognition by all that chaos. The result should be a blurry, depolarized mess where any measurable signal approaches zero.

But that’s not what happened.

Instead, the researchers observed something stunning: a large-scale, robust separation of light based on its spin. The chaotic system wasn’t destroying the signal—it was amplifying it into a pattern visible across centimeters, the largest such effect ever observed in disordered structures.

The disorder, it turned out, was doing the work.

The Mechanism: Why Stillness Fails

Here’s where it gets beautiful. In a perfectly ordered system—particles frozen in place, everything aligned and controlled—the scattered light waves maintain fixed relationships with each other. When one wave’s crest meets another wave’s trough, they cancel out. This destructive interference is relentless and comprehensive in static systems. The very perfection of the order becomes its downfall.

But in the Brownian system, the particles are moving so fast that by the time one scattered light field reaches the detector, all the particles have shifted to entirely new positions. The phase relationships between light waves become completely random over time. The destructive interference still happens, but it happens at random moments and random places. Over the two-second camera exposure (roughly 2,800 times longer than the system’s coherence time), these random destructive effects cancel each other out, while the fundamental underlying pattern accumulates and reveals itself.

The chaos acts as a perfect temporal filter, stripping away the noise of coherent interference and leaving only the signal.

It’s worth sitting with this for a moment. We’ve built an entire technological civilization on the principle of imposing order to extract signals from noise. Here, the noise is creating the conditions for the signal to emerge.

What This Means Beyond the Lab

The immediate practical application is remarkable: a new way to measure nanoparticle properties with 89-99% accuracy using simple equipment—just a laser, a container, and a spectrometer. No billion-dollar fabrication facilities, no clean rooms, no painstaking construction of engineered metamaterials. The chaos does the engineering for you.

But the deeper implications ripple outward. This discovery suggests we should be looking for similar effects wherever dynamical disorder meets subtle physical properties. Sound waves in turbulent fluids. Quantum systems with thermal fluctuations. Any situation where we’ve assumed that randomness was the problem might actually be where randomness provides the solution.

It’s a paradigm shift in how we think about measurement and observation. We’ve always known that averaging over many measurements can reduce random errors. But this is different. This is using the temporal chaos itself as an active component of the measurement system—not something to be overcome, but something to be harnessed.

The Larger Pattern

There’s something almost philosophical here about how truth reveals itself. We tend to think that seeing clearly requires stillness, control, perfect conditions. Stand perfectly still. Hold your breath. Eliminate all variables. Only then can you observe what’s real.

But some truths only emerge in motion. Some patterns only become visible when you allow systems to fluctuate freely. The rigidity we think protects our observations can actually obscure them.

I think about this in contexts far removed from physics labs. How many times do we demand perfect conditions before we’re willing to see what’s actually there? How often do we mistake the absence of chaos for the presence of clarity?

The researchers who made this discovery weren’t trying to eliminate the Brownian motion. They were looking to see what it might reveal. That shift in perspective—from disorder as enemy to disorder as potential tool—opened up an entirely new phenomenon.

Living in the Mess

We live in times that feel increasingly chaotic. Information flows unpredictably. Systems we thought were stable prove fragile. The pace of change seems to accelerate beyond our ability to impose order on it.

The temptation is always to hunker down, to try to control more variables, to demand stillness before we’re willing to observe. But what if some of the patterns we most need to see will only reveal themselves in the motion? What if the chaos isn’t something to be eliminated before the real work begins, but is actually part of the mechanism through which truth emerges?

This isn’t an argument for embracing disorder for its own sake. The Brownian Spin-Locking Effect works because the researchers understood both the order (the fundamental physics of how light scatters off spherical particles) and the disorder (the thermal chaos of Brownian motion). They didn’t choose one over the other. They found the place where they work together.

There’s a gentleness in this approach that I find compelling. It’s not about forcing nature into the shapes we find convenient. It’s about observing carefully enough to see when nature’s apparent messiness is actually doing sophisticated work we couldn’t have designed ourselves.

The gold nanoparticles are still jittering chaotically. The water molecules are still bombarding them from all sides. Nothing has been tamed or controlled in the traditional sense. But by observing from the right angle, with the right tools, at the right timescale, the researchers found that the chaos was already organizing itself into patterns—it just needed someone patient enough to see them.

Perhaps that’s the real discovery: not that we can impose order on chaos, but that chaos might already contain more order than we ever gave it credit for. We just have to learn where to look, and more importantly, we have to be willing to look while everything is still moving.

The particles are dancing. They’ve always been dancing. We’ve finally learned how to see the pattern in their motion.

Link References

Episode Links

Youtube

Available for broadcast on PRX

Other Links to Heliox Podcast

YouTube

Substack

Podcast Providers

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Patreon

FaceBook Group

STUDY MATERIALS

Briefing

Executive Summary

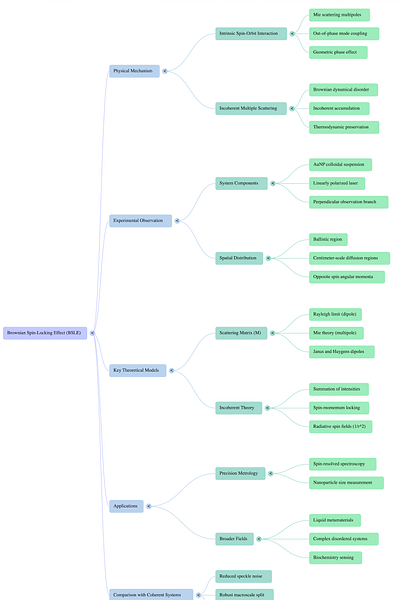

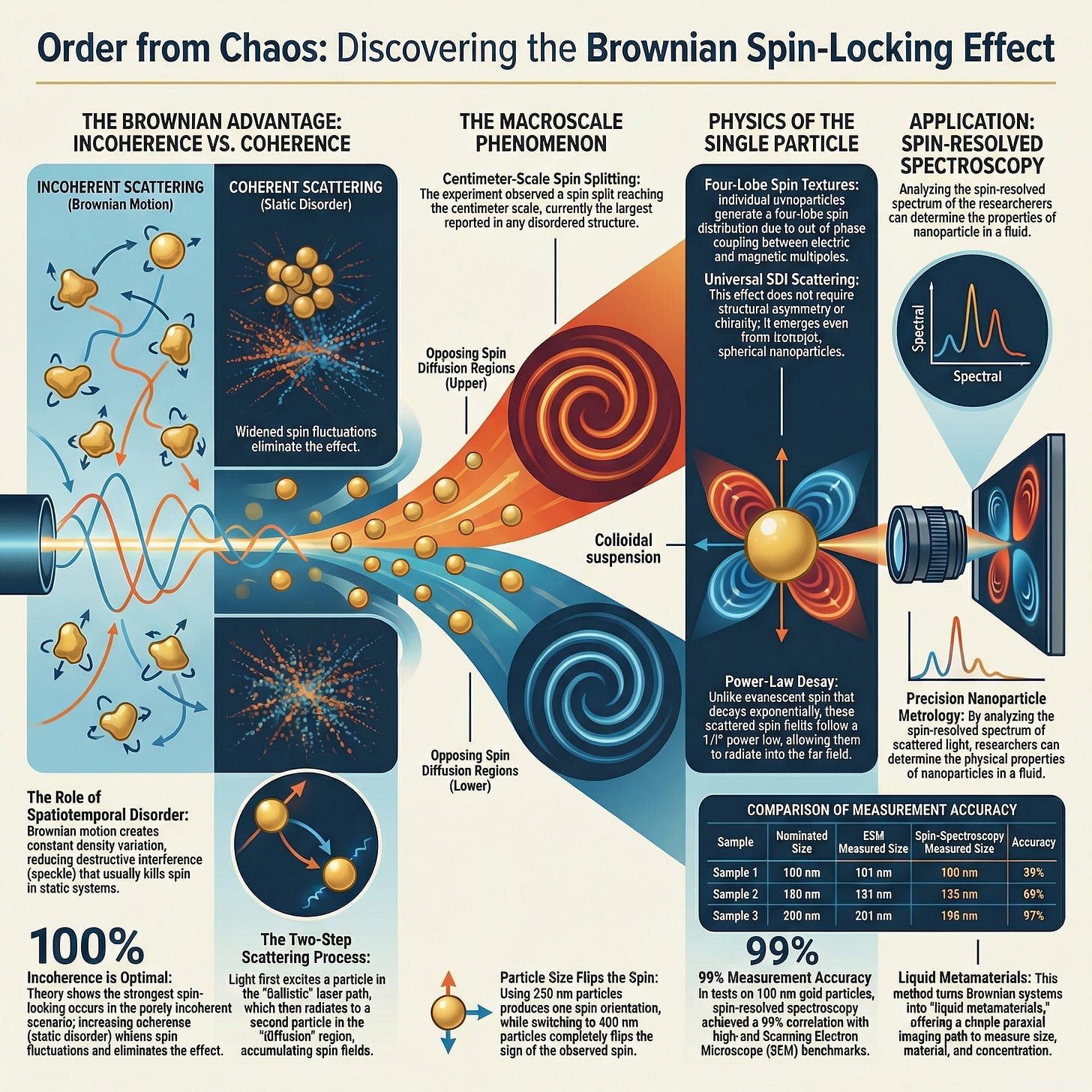

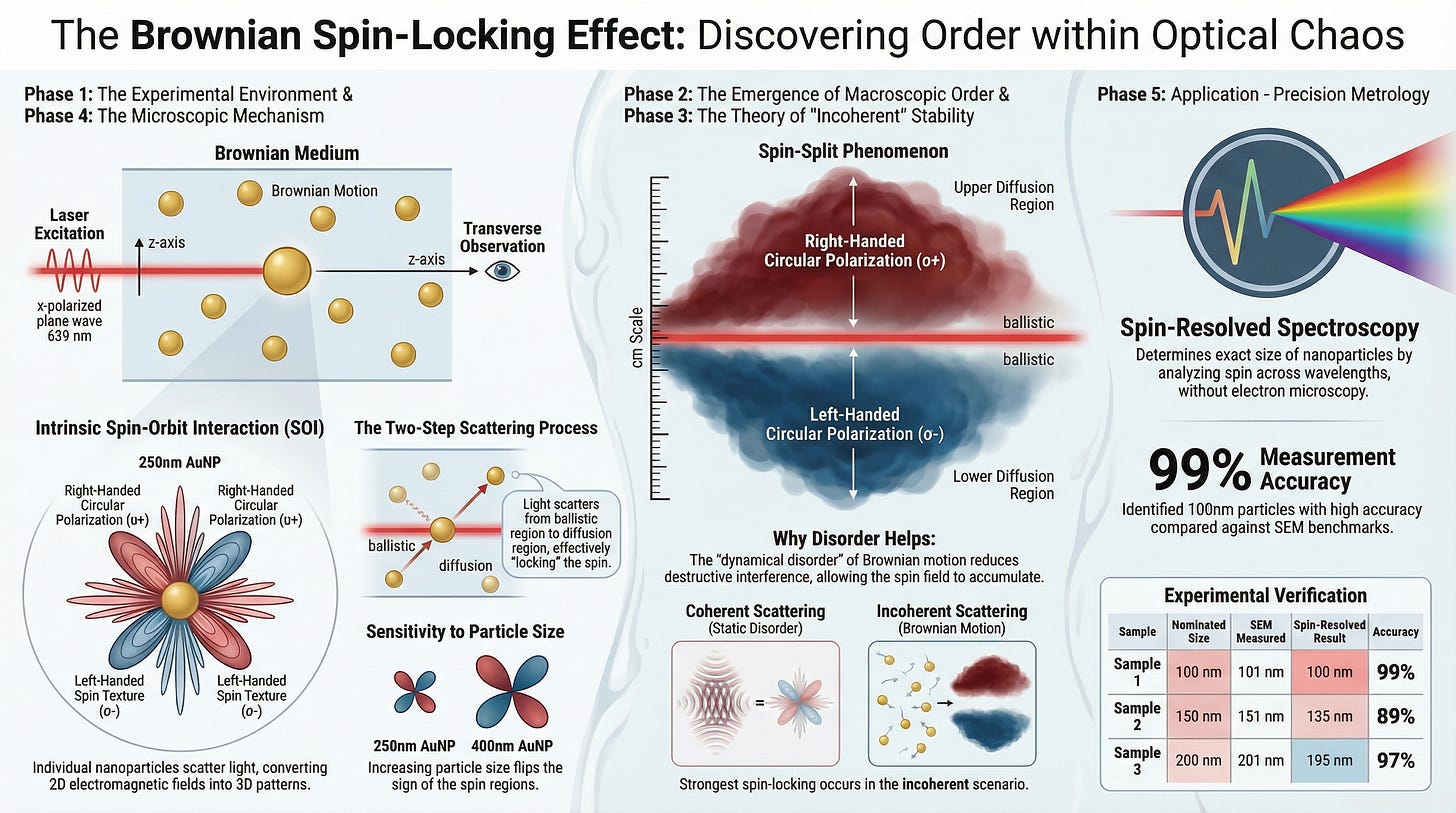

A novel, large-scale optical phenomenon termed the Brownian spin-locking effect (BSLE) has been observed in a spatiotemporally disordered medium. The research demonstrates that when light interacts with a colloidal suspension of nanoparticles undergoing Brownian motion, the scattered light spontaneously separates into two distinct, macroscopic regions of opposite spin (circular polarization). This effect is counter-intuitive, as the high degree of disorder in a Brownian system would typically be expected to randomize and eliminate such delicate spin-dependent phenomena.

The physical mechanism is twofold, arising from a combination of intrinsic spin-orbit interactions (SOI) at the single-particle level and the critical role of incoherent multiple scattering. Every nanoparticle, when scattering light, ubiquitously generates a radiative spin field. The erratic, thermal motion of the particles ensures the scattering is incoherent, which prevents destructive interference and allows these individual spin fields to accumulate over a massive number of particles. This accumulation results in a robust, centimeter-scale spin separation, the largest reported to date in disordered structures.

The discovery provides a new experimental platform for exploring macroscale spin behaviors of diffused light. Its significance is demonstrated through a practical application: a spin-resolved optical spectroscopy technique for precision metrology. This method successfully measured the size of gold nanoparticles with high accuracy (up to 99%), showcasing its potential for broad applications in chemistry, biology, and material science.

1. The Phenomenon of Brownian Spin-Locking (BSLE)

1.1 Core Observation

The central finding is the large-scale, robust spin-locking effect of light scattered from a Brownian medium. In a typical experiment, a linearly polarized laser beam impinges on a colloidal suspension of nanoparticles. When observed from a direction perpendicular to the incident beam, the scattered light naturally divides into two large, distinct regions:

• A “ballistic region” that spatially overlaps with the laser beam.

• Two “diffusion regions” on opposite sides of the laser, each exhibiting a homogeneous but opposite spin angular momentum. For instance, the upper diffusion region may show right-handed circular polarization, while the lower region shows left-handed circular polarization.

This spin separation is exceptionally large, with each spin-polarized region reaching a centimeter scale, and exhibits very small spatial fluctuation despite the thermodynamic nature of the system.

1.2 Experimental Verification

The effect was systematically verified through a series of experiments.

• Primary Experiment: An x-polarized plane wave laser (639 nm wavelength, ~2 mm beam width) was directed through a glass container of spherical gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) suspended in water at room temperature (~25°C). The average diameter of the AuNPs was 250 nm.

• Origin Confirmation: The phenomenon was confirmed to originate from the properties of the Brownian scattering system. When the 250 nm AuNPs were replaced with a different sample of 400 nm AuNPs, the sign of the spin in the diffusion regions was observed to flip completely.

• Generality: The BSLE is a universal phenomenon, also demonstrated with nanoparticles of different materials (e.g., Fe3O4) and varying concentrations. The shape of the sample container (cylindrical vs. cubic) was shown to have a negligible influence on the results.

1.3 Conceptual Illustration

Conceptually, a plane wave laser enters the colloidal suspension, which is composed of many spherical gold nanoparticles in constant Brownian motion. The interaction results in the nanoparticles in the upper diffusive region radiating light with a right-handed circular polarization (σ+), while nanoparticles in the lower diffusive region radiate light with a left-handed circular polarization (σ−).

2. Underlying Physical Mechanism

The BSLE arises from the interplay of two essential physical processes: the intrinsic spin-orbit interaction of scattering from individual nanoparticles and the incoherent nature of multiple scattering in a Brownian medium.

2.1 Intrinsic Spin-Orbit Interaction (SOI) from Single Nanoparticles

The origin of the spin separation lies in the fundamental light-matter interaction at the level of a single particle.

• Universal Effect: When a linearly polarized light excites an isotropic, spherical nanoparticle, the scattered field becomes spin-dependent in observation directions perpendicular to the incident momentum. This does not require any structural anisotropy or chirality in the particle.

• Radiative Spin Fields: As the nanoparticle size increases beyond the Rayleigh limit, multipole responses (e.g., electric quadrupole, magnetic dipole) emerge. Out-of-phase couplings between these harmonic modes of Mie scattering cause the scattered spin fields to become radiative, meaning they propagate to the far field. The spin magnitude decays with distance as a power-law function (|s| 1/r²).

• Four-Lobe Spin Texture: For a 250 nm AuNP, the scattered spin field forms a characteristic four-lobe texture around the particle. The upper and lower lobes exhibit opposite spin orientations (spin up vs. spin down), which form the basis for the macroscopic diffusion regions observed in the experiment.

2.2 The Critical Role of Incoherent Scattering

While single-particle SOI creates the initial spin asymmetry, the spatiotemporal disorder of the Brownian system is crucial for its macroscopic manifestation.

• Suppression of Coherence: In a static or coherent disordered system, destructive interference between scattered waves would create random speckle patterns and eliminate any large-scale spin phenomena.

• Preservation by Disorder: The erratic movement of nanoparticles in a Brownian system leads to constant density variations and incoherent multiple scattering. This thermodynamic disorder effectively averages out and reduces destructive interference.

• Accumulation of Spin: By mitigating interference, the incoherent scattering preserves the fundamental spin distribution generated by individual nanoparticles. The spin field is then constantly accumulated through scattering from a massive number of particles, resulting in the observed large-scale, homogeneously distributed spin regions. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements confirmed the system’s incoherent nature, showing a short coherence time of τc ≈ 0.7 ms, well below the camera’s acquisition time of 2 seconds.

3. Theoretical Modeling and Validation

A scattering theory was established to explain the experimental observations, successfully capturing the essential physics of the BSLE.

3.1 Incoherent Multiple Scattering Theory

The complex system was simplified into a two-step scattering model: (i) an incident laser excites a nanoparticle in the ballistic region, which acts as a radiation source, and (ii) this radiation excites another nanoparticle in the diffusion region. To model the incoherence, the final intensities for right-handed (IR) and left-handed (IL) polarizations were summed over all nanoparticles, rather than their fields.

• Agreement with Experiment: Calculations using this incoherent theory for N = 6×10⁵ AuNPs showed “excellent agreements” with the experimentally observed intensity and spin distributions.

• Statistical Match: The model also replicated the spatial statistics observed experimentally. The intensity probability followed a typical incoherent property (fitted by a Burr distribution), and the spin statistics were characterized by two narrow Beta distributions with opposite central values.

3.2 Comparison with Coherent Theory

To highlight the importance of incoherence, a comparative calculation was performed assuming coherent scattering with the same nanoparticle arrangement.

• Drastically Different Results: The coherent model produced results drastically different from both the incoherent model and the experimental observations. The output was dominated by random speckles caused by destructive interference, and the spin-locking phenomenon was “significantly reduced.”

3.3 Coherence Evolution Model

A theoretical model was developed to show the evolution from a fully incoherent to a coherent system. The results clearly demonstrate that the strongest and clearest spin-locking phenomenon occurs in the fully incoherent scenario (characteristic of Brownian motion). As the degree of coherence increases, spin fluctuations increase, the spin distributions widen, and the BSLE is progressively reduced and ultimately eliminated.

4. Application: Spin-Resolved Spectroscopy for Nanoparticle Sizing

The discovery of BSLE was leveraged to develop a novel metrology technique based on the principle that the spin-resolved optical field carries detailed information about the scattering nanoparticles.

4.1 Principle and Methodology

A spin-resolved optical spectroscopy method was developed to measure the size of AuNPs. The technique involves:

1. Illuminating the nanoparticle suspension with a broadband laser source.

2. Using a spectrometer to capture the spin-resolved spectrum, sx(λ) = [IR(λ) - IL(λ)] / [IR(λ) + IL(λ)], from a location in one of the diffusion regions.

3. Comparing the experimentally observed spectrum, sx(λ), with a library of theoretical spectra, sx, theory(D, λ), calculated using the incoherent scattering theory for various particle diameters D.

4. The particle size is determined by finding the value of D that yields the highest correlation between the experimental and theoretical spectra.

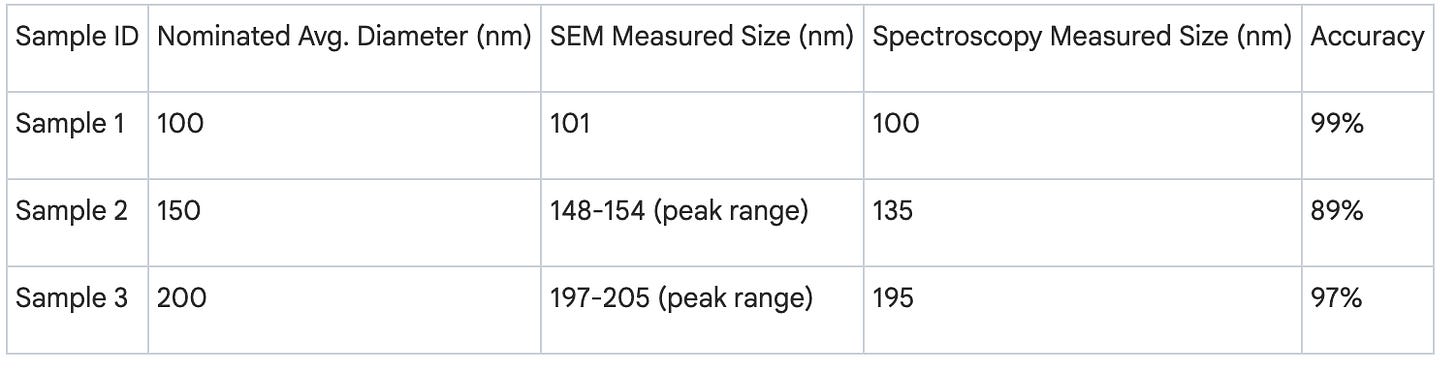

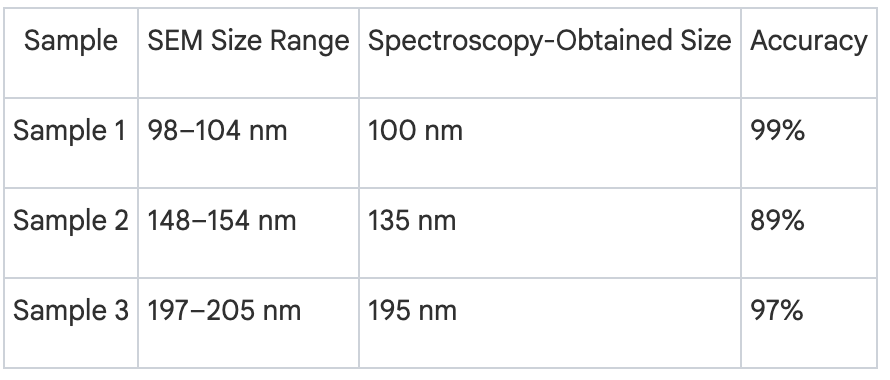

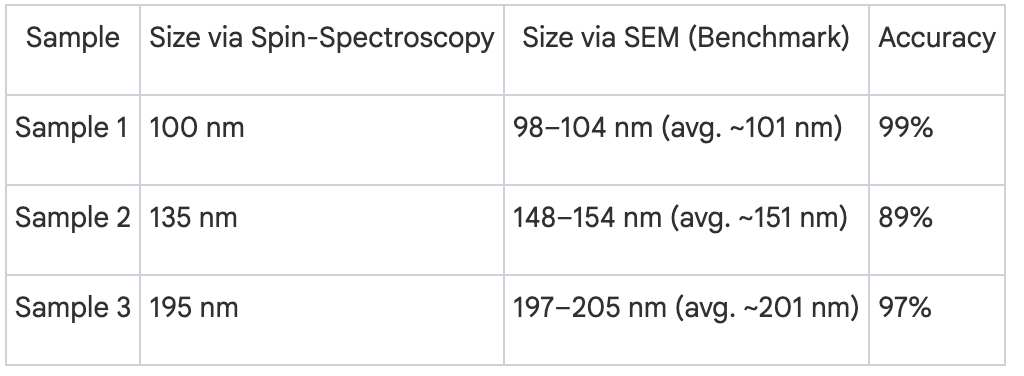

4.2 Experimental Demonstration and Accuracy

The method was validated against benchmark measurements from a scanning electron microscope (SEM) for three different AuNP samples. The results showed a high degree of accuracy.

The precision of this technique can be further improved by expanding the detection wavelength range or employing feedback optimization algorithms.

5. Further Insights and Future Directions

5.1 Key Properties of the BSLE

• Polarization Dependence: The orientation of the macroscopic spin pattern depends directly on the polarization of the incident linear light. Rotating the incident polarization causes a corresponding rotation of the four-lobe pattern, which is reflected in the macroscopic spin distribution.

• Observation Direction: Consistent with the four-lobe spin texture from a single particle, observing the scattered light from opposite directions (e.g., +x vs. -x) results in a flipped spin pattern.

• Robustness: The BSLE is robust against high nanoparticle concentrations, although the spin effect is weakened over longer propagation distances due to depolarization from complex multiple scattering. The effect is also independent of the incident laser’s beam waist.

5.2 Future Research Avenues

The study of the BSLE opens several promising avenues for future research:

• Dynamical Effects: Investigating the dynamics of the spin effects using fast optical detection methods or by slowing the Brownian motion via temperature or viscosity control.

• Liquid Metamaterials: Utilizing the Brownian system as a “liquid metamaterial.” By suspending engineered nanostructures with customized sizes and shapes (”meta-molecules”) that are thermally fluctuated, it may be possible to achieve exotic and tunable light-matter interactions.

• Broader Applications: Developing the spin-resolved optical method to detect not only size but also material composition and other properties of nanoparticles, with wide-ranging applications in chemistry, micromechanics, and biology.

Quiz & Answer Key

Answer each question in 2-3 sentences based on the provided source material.

1. What is the Brownian spin-locking effect (BSLE) as observed in the study?

2. Describe the two fundamental physical mechanisms that combine to produce the BSLE.

3. How does the coherence of the scattering process influence the observation of the BSLE?

4. What are the key components of the experimental setup used to observe and measure the BSLE?

5. How did the researchers experimentally confirm that the BSLE is directly related to the physical properties of the nanoparticles?

6. Explain the difference in the scattered spin field’s behavior for very small particles (Rayleigh limit) versus larger nanoparticles.

7. What is spin-resolved spectroscopy, and what practical application was demonstrated for this technique?

8. Why is the BSLE described as a “robust” phenomenon?

9. What is the “four-lobe spin texture,” and what is its significance for observing the BSLE from different directions?

10. Compare the outcomes of the incoherent versus coherent scattering theories used to model the BSLE.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Answer Key

1. The Brownian spin-locking effect (BSLE) is a large-scale phenomenon where light scattered by a Brownian medium divides into two distinct diffusion regions. When observed perpendicular to the incident laser’s momentum, one region is associated with a right-handed spin polarization and the other with a left-handed spin polarization.

2. The BSLE arises from two main aspects: the intrinsic spin-orbit interactions (SOIs) from individual nanoparticles and the incoherent multiple scattering from these nanoparticles. The intrinsic SOI generates radiative spin fields, and the thermodynamic disorder from Brownian motion allows these spin fields to accumulate without destructive interference.

3. The BSLE is strongest in the incoherent scenario, which is characteristic of a Brownian system. As the degree of coherence increases, destructive interference between waves creates random speckles and spin fluctuations, which significantly reduce and eventually eliminate the spin-locking phenomenon.

4. The experimental setup consists of a linearly polarized laser (639 nm) impinging on a sample of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) suspended in water. The observation branch is set perpendicular to the incident direction and uses a lens system, a quarter-wave plate, and a post-polarizer to capture and analyze the intensity of opposite spin polarizations on a camera.

5. Researchers verified the effect’s dependence on nanoparticle properties by performing the same experiment with a different sample of AuNPs with an average diameter of 400 nm instead of 250 nm. This change resulted in a complete flip in the sign of the observed spin in the diffusion regions, indicating the nanoparticles’ properties play a critical role.

6. For extremely small particles in the Rayleigh limit, the scattered field is an electric dipole radiation with purely transverse spin that is imbedded in the evanescent field and decays with a power-law of 1/r³. For larger nanoparticles, multipole responses occur, causing the scattered spin fields to become radiative, partially aligned with the Poynting vector, and decay as 1/r².

7. Spin-resolved spectroscopy is a method developed to measure the size of nanoparticles by analyzing the spin spectrum, sx(λ), of the scattered light. In the study, it was used to measure the size of three different AuNP samples with accuracies of 99%, 89%, and 97% when compared to SEM benchmarks.

8. The BSLE is considered robust because it survives even in high concentrations of nanoparticles where complex multiple scattering dominates. It is also not impacted by the beam waist of the incident laser, appearing similarly for both plane wave and focused beam illuminations.

9. The “four-lobe spin texture” describes the spin distribution pattern produced by scattering from a single nanoparticle. Because of this pattern, flipping the observation direction (e.g., from +x to -x) results in an observed flip in the macroscopic spin distribution, a phenomenon confirmed by the experiments.

10. The incoherent scattering theory, which sums the intensities from many nanoparticles, shows excellent agreement with experimental observations, predicting the distinct, homogeneously distributed spin regions. In contrast, the coherent scattering theory, which sums the fields, predicts a drastically different result with many random speckles and a significantly reduced spin-locking effect due to destructive interference.

Essay Questions

Construct detailed, essay-format answers to the following questions. Answers are not provided.

1. Discuss the role of thermodynamic disorder (incoherent scattering) versus coherent disorder in the emergence of the Brownian spin-locking effect. Why does the former enhance the effect, leading to centimeter-scale spin separation, while the latter diminishes it?

2. Explain the physical origin of the generic spin radiation from a single nanoparticle, linking it to spin-orbit interactions, Mie scattering theory, and multipole responses. Trace how this microscopic effect is preserved and accumulated through multiple incoherent scattering events to produce the observed macroscopic phenomenon.

3. Detail the experimental methodology of spin-resolved spectroscopy as described in the paper. Analyze its potential as a precision metrology tool for nanoparticle characterization by discussing its demonstrated accuracy, its underlying principles, and the suggested methods for further improving its precision.

4. Compare and contrast the spin-momentum locking relationship for an electric dipole emitter in three-dimensional space with established relations for two-dimensional evanescent waves. Using the provided theoretical framework, explain how different multipole components (e.g., magnetic dipole, quadrupoles) and their combinations (e.g., Huygens and Janus dipoles) alter the spin properties of scattered light.

5. Explore the potential future research directions and practical applications for the Brownian spin-locking effect as outlined in the paper’s discussion. Consider its implications for fields such as material science, biology, and the fundamental study of wave phenomena in other classical and quantum systems.

Glossary of Key Terms

Ballistic Region

The spatial region in the scattering medium that directly overlaps with the incident laser beam.

Brownian Motion

The erratic, random movement of particles suspended in a fluid resulting from their stochastic collisions with fluid molecules. The mean squared displacement of these particles is proportional to time.

Brownian Spin-locking Effect (BSLE)

A large-scale phenomenon where light interacting with a Brownian medium produces two macroscale diffusion regions, each associated with an opposite spin, observed perpendicular to the incident wave’s momentum.

Coherent Scattering

A scenario where scattered waves maintain a fixed phase relationship, leading to constructive and destructive interference. In the context of the BSLE, this leads to random speckles and diminishes the spin-locking phenomenon.

Diffusion Region

The regions on opposite sides of the central laser path where light that has been scattered multiple times within the medium is observed. In the BSLE, these regions exhibit opposite spin angular momenta.

Dynamical Light Scattering (DLS)

An optical technique used to measure the size of nanoparticles by analyzing the intensity fluctuations of scattered light caused by the diffusion properties of Brownian particles.

Huygens Dipole

A specific multipole response of a particle where the Mie coefficients are equal (a1 = b1), satisfying a Kerker condition. The spin-momentum locking relation ∇ × S = kP works for a Huygens dipole, ignoring higher-order terms.

Incoherent Multiple Scattering

The process where light is scattered multiple times by dynamically moving particles (like in Brownian motion), causing the phase relationships between scattered waves to be randomized. This process preserves the spin distribution from single nanoparticles and allows it to accumulate.

Janus Dipole

A specific multipole response defined by the Mie coefficient relation a1 = ib1. The spin angular momentum (SAM) of a Janus dipole is a far-field effect, meaning it can be detected at distances much greater than the wavelength of light.

Mie Scattering

A theory that describes the scattered electromagnetic field of a plane wave by a spherical particle. The solution is expressed as a superposition of vector spherical harmonics, corresponding to a multipole expansion.

Poynting Vector

A vector representing the directional energy flux density (the rate of energy transfer per unit area) of an electromagnetic field, defined as P = (1/2) Re[E × H*].

Rayleigh Scattering

The simplest case of Mie scattering, which applies when the scattering particle’s size is very small compared to the incident wavelength. It is also known as the electric dipole approximation.

Spin (Normalized, sx)

A measure of the circular polarization of light, characterized by the formula sx = (IR - IL) / (IR + IL), where IR and IL are the intensities for right- and left-handed circular polarizations, respectively.

Spin Angular Momentum (SAM) Density

A vector quantity describing the local density of spin angular momentum in an electromagnetic field, defined as S = Im[ε₀E* × E + μ₀H* × H].

Spin-orbit Interactions (SOIs)

The interplay between the spin (polarization) and orbital (spatial propagation) degrees of freedom of light. In the BSLE, intrinsic SOIs from individual nanoparticles generate radiative spin fields.

Spin-resolved Spectroscopy

An optical technique developed in the study to measure the size of nanoparticles. It involves using a broadband laser source and a spectrometer to capture the spin spectrum, sx(λ), which is then correlated with theoretical spectra for different particle sizes.

Thermodynamic Disorder

A state of spatiotemporal disorder characteristic of a Brownian system, arising from the erratic motion of particles driven by thermal fluctuations. This type of disorder is crucial for preserving and accumulating spin fields in the BSLE.

Timeline of Main Events

1.0 An Unexpected Discovery: Uncovering Spin Order in a Disordered System

In the realm of physics, a disordered system is conventionally seen as an agent of chaos, a medium that scrambles the properties of any wave passing through it. Brownian systems, characterized by the erratic, thermally-driven motion of particles, are a prime example of such spatiotemporal disorder. Standard scientific intuition dictates that when light interacts with these systems, its properties—particularly its spin, the intrinsic angular momentum of light that manifests as circular polarization (either right-handed or left-handed)—should be thoroughly randomized. This is because in coherent, static disorder, the delicate symmetry-breaking conditions required for spin separation become ill-defined and are averaged to zero. It was therefore a profound scientific shock when researchers observed a robust, large-scale spin-locking effect emerging from the very heart of a disordered Brownian medium. This finding presented a sharpened paradox: not just order from chaos, but order because of chaos.

This newly discovered phenomenon was termed the Brownian spin-locking effect (BSLE). The core observation is that when light scatters within a Brownian medium, it naturally separates into two distinct diffusion regions. Remarkably, each of these macroscale regions becomes associated with an opposite and well-defined light spin. Instead of randomizing the polarization, the dynamically disordered system acts as a sorter, partitioning the scattered light based on its spin angular momentum.

The effect is striking in its visual simplicity. As conceptually illustrated in Figure 1 of the original research, when a plane wave laser enters a colloidal suspension of nanoparticles, the chaotic scattering process gives rise to a highly ordered output. The countless nanoparticles in the upper diffusion region collectively radiate light with right-handed circular polarization. Simultaneously, the nanoparticles in the lower region radiate light with left-handed circular polarization. This spontaneous and large-scale division of spin creates a clear, stable pattern of polarization where none was expected.

This unforeseen effect, manifesting at a scale easily visible to the naked eye (reaching up to a centimeter), fundamentally challenged existing assumptions about light-matter interactions in complex disordered media. It immediately signaled that a deeper physical mechanism was at play, one that not only survived but thrived in a dynamically fluctuating environment. This discovery necessitated a new line of theoretical and experimental investigation to uncover its origins, characterize its behavior, and explore its potential applications.

2.0 Characterizing the Effect: Systematic Experimental Investigation

Faced with an anomaly that defied conventional wisdom, the next step in the scientific method was to interrogate it with rigorous, systematic experimentation. To confirm and characterize the BSLE, researchers designed a series of precise experiments to isolate contributing factors, verify the system’s properties, and establish the effect’s robustness. This section details the experimental configuration and the key findings that provided the empirical foundation for this discovery.

2.1 Experimental Configuration and Initial Observations

To isolate and scrutinize this bizarre effect, the researchers constructed a meticulously controlled optical experiment. As depicted in Figure 2A, a 639 nm laser producing an x-polarized plane wave was directed into a glass sample container holding a colloidal suspension of spherical gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) in water. To observe the scattered light, an imaging system was positioned perpendicular to the direction of the incident laser beam, an orthogonal axis critical to revealing the spin separation.

Using a sample of AuNPs with an average diameter of 250 nm, the initial observations confirmed the new effect. As shown in the experimental images (Figures 2D and 2E), the scattered light formed a distinct intensity distribution composed of a bright, central ballistic region, where the laser beam passed directly through, flanked by two expansive diffusion regions. When the spin of the light in these regions was measured—quantified by the normalized spin sx = (IR - IL) / (IR + IL), where IR and IL are the intensities for right- and left-handed circular polarizations—a clear division emerged. The upper diffusion region exhibited a uniform positive spin, while the lower region showed the exact opposite spin, creating a robust, large-scale split.

2.2 Verifying the Role of Nanoparticles and Brownian Motion

To prove this was not a trick of the light or an artifact of the optical setup, the researchers devised a definitive test. They replaced the 250 nm AuNPs with a different sample containing AuNPs of a larger average diameter (400 nm). The result was both immediate and profound: the entire spin pattern flipped (Figures 2F and 2G). This was the smoking gun, demonstrating that the spin-locking phenomenon originated directly from the physical properties of the nanoparticles within the Brownian system itself.

The “Brownian” nature of the system was also experimentally confirmed. Using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), researchers measured the intensity fluctuations of the scattered light over time. The results (Figure 2C) revealed a coherence time of approximately τc ≈ 0.7 milliseconds, a hallmark of Brownian motion. The camera’s acquisition time was set to about 2 seconds—thousands of times longer than the coherence time. This ensured that the captured images averaged over countless random configurations of the nanoparticles, confirming that the observed spin-locking was a stable property of the incoherent scattering process, not a fleeting interference pattern.

This body of experimental evidence established the BSLE as a real and reproducible phenomenon, paving the way for the development of a theoretical framework capable of explaining how such order could arise from disorder.

3.0 The Theoretical Breakthrough: Explaining BSLE with Incoherent Scattering

Modeling the complex, dynamic interactions of light with trillions of randomly moving particles presents a formidable theoretical challenge. This was the moment of revelation, where theory had to explain the experimental anomaly. The researchers developed a simplified yet powerful incoherent multiple scattering theory that successfully accounted for the observed macroscale spin effect by focusing on two essential physical processes.

The model cleverly simplifies the chaos by simulating a “chain reaction” of light. By calculating the outcome of an elemental two-particle interaction and summing the intensities (not the fields) from all possible pairs, the model reconstructs the entire macroscopic pattern:

• Two-Step Scattering Process: The model first calculates a fundamental two-step interaction. (1) An incoming photon from the laser excites a nanoparticle in the central ballistic region. (2) This first particle then re-radiates light, which in turn excites a second nanoparticle located in one of the outer diffusion regions.

• Incoherent Superposition: Crucially, for an incoherent system like a Brownian medium, the final result is determined not by summing wave fields (which would lead to interference) but by summing their intensities. The theory calculates the intensity contributions for spin-up (right-handed) and spin-down (left-handed) states separately for every two-step process and sums them over all possible particle pairs. The final macroscale spin pattern is then determined from their difference.

The predictions of this incoherent scattering theory showed “excellent agreements” with the experimental data. The calculated intensity and spin distributions (Figure 3B) closely matched the camera-captured images (Figures 2D and 2E). Furthermore, the model accurately reproduced the statistical distributions of intensity and spin observed experimentally (Figure 3A), confirming its physical accuracy.

3.1 The Critical Role of Incoherence

The failure of a competing model was as important as the success of this one. To prove that disorder was the key ingredient, the researchers performed a comparative calculation assuming the particles were static, or coherent. The results (Figure 3C) were drastically different. Instead of clean diffusion regions, the coherent model’s output was almost entirely washed out by a noisy blizzard of interference speckles, failing spectacularly to reproduce the clean, robust separation seen in the lab.

A simulated evolution from a fully incoherent to a coherent system (Figure 3D) drove the point home. The simulation revealed a clear trend: the strongest and cleanest spin-locking effect occurs in the fully incoherent (Brownian) scenario. As coherence increases, the effect is progressively degraded by interference-driven fluctuations and eventually eliminated.

This theoretical breakthrough revealed that the chaotic motion of the nanoparticles was not a bug, but a feature—a dynamic filter that allows the fundamental spin signature of each individual particle to emerge on a macroscopic scale.

4.0 The Fundamental Origin: Generic Spin Radiation from Single Particle Scattering

The bridge between the macroscale spin separation and its microscopic cause is the phenomenon of spin-orbit interaction (SOI) of light. This interaction is not a peculiarity of the collective system but an intrinsic property of light scattering from a single, individual nanoparticle. The collective BSLE is the large-scale manifestation of this fundamental, microscopic effect, summed over countless particles.

This single-particle spin effect is remarkably universal. It does not require nanoparticles with special shapes (structural anisotropy) or inherent handedness (chirality). It emerges even for simple, isotropic spherical nanoparticles when they are excited by linearly polarized light, arising from the coupling between the particle’s induced electric dipole, magnetic dipole, and quadrupole moments. During scattering, a portion of the light’s spin becomes aligned with its direction of propagation (the Poynting vector, which indicates the flow of electromagnetic energy). These scattered spin fields are radiative, decaying with a power-law function (1/r²) that allows them to survive and contribute to multiple scattering events.

A theoretical calculation for a single gold nanoparticle (D = 250 nm) reveals the precise nature of this spin radiation (Figure 4A). The scattered light organizes into a distinct four-lobe spin texture around the particle, where reddish colors represent spin-up states and bluish colors represent spin-down states. This microscopic pattern is the direct source of the macroscopic observation. The dashed circular sectors in the theory diagram correspond to the angular regions captured by the camera lens in the experiment, linking the single-particle theory directly to the observed upper and lower diffusion regions.

To validate this connection, researchers tested the system’s response to different incident light polarizations. The results show a perfect match between the single-particle theory and the collective experimental observation.

Table 1: Validation of the Single-Particle Spin-Orbit Interaction Theory | Incident Polarization | Predicted Spin Pattern (Theory) | Observed Spin Pattern (Experiment) | | :--- | :--- | :--- | | Horizontal (x-polarized) | Red (up) in the upper lobe, Blue (down) in the lower lobe. | The experiment shows a red upper diffusion region and a blue lower diffusion region, matching the theory. | | Vertical (y-polarized) | Blue (down) in the upper lobe, Red (up) in the lower lobe. | The experiment confirms this reversal, with a blue upper region and a red lower region. |

With the underlying physics validated from the microscopic single-particle level to the macroscopic collective effect, this newfound understanding could be leveraged for a novel and practical application.

5.0 A Practical Application: Spin-Resolved Spectroscopy for Nanoparticle Sizing

Translating a fundamental scientific discovery into a practical technology is a key goal of modern research. The Brownian spin-locking effect, by linking a macroscopic optical signal to the microscopic properties of nanoparticles, provides a new tool for precision metrology. Researchers developed a proof-of-concept spin-resolved spectroscopy method capable of accurately measuring nanoparticle size.

The methodology for this novel technique is direct and elegant. Instead of a single-wavelength laser, a broadband laser source illuminates the sample. A spectrometer then captures the spin spectrum, sx(λ), which describes how the spin-locking effect varies with the wavelength of light. This experimentally measured spectrum is compared with a library of theoretical spectra calculated for different particle diameters (D). The particle size that yields the highest correlation between the experimental and theoretical spectra is identified as the measured result.

To validate this technique, three different AuNP samples were tested, with the results benchmarked against measurements from a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The results, presented in Figure 5, demonstrated high accuracy:

1. Sample 1: The highest correlation from spin-resolved spectroscopy occurred for D = 100 nm, showing 99% accuracy compared to the SEM-measured size distribution of 98–104 nm (average 101 nm).

2. Sample 2: The highest correlation occurred for D = 135 nm, demonstrating 89% accuracy compared to the SEM-measured size distribution of 148–154 nm (average ~151 nm).

3. Sample 3: The highest correlation occurred for D = 195 nm, resulting in 97% accuracy compared to the SEM-measured size distribution of 197–205 nm (average ~201 nm).

This successful demonstration established spin-resolved spectroscopy as a viable optical method for nanoparticle sizing, showcasing the potential for this fundamental discovery to evolve into a valuable tool for science and industry.

6.0 Conclusion and Future Outlook

This body of research presents the discovery and explanation of the Brownian spin-locking effect—a robust, macroscale ordering of light’s spin that emerges from a spatiotemporally disordered medium. The phenomenon is traced back to its fundamental origin: the interplay between the intrinsic spin-orbit interactions of light scattering from individual nanoparticles and the incoherent multiple scattering that dominates in a Brownian system. The successful application of this effect in a novel, spin-resolved spectroscopy for nanoparticle sizing confirms its practical potential.

This work opens up several exciting avenues for future research and technological development, moving from fundamental physics to applied material science.

• Broadened Applications: The spin-resolved optical method could be expanded beyond sizing to measure other crucial nanoparticle properties, such as their material composition and shape. This would create a versatile, non-invasive tool for fields like chemistry, biology, and materials science.

• Dynamic Spin Effects: The current study focused on the time-averaged, stable spin pattern. Future work could investigate the system’s rapid dynamics by using fast optical detection methods or by slowing down the Brownian motion itself, for instance by controlling the medium’s temperature or viscosity.

• Liquid Metamaterials: The nanoparticles in a Brownian system can be viewed as “thermally fluctuated meta-molecules.” By using engineered nanostructures with customized shapes and properties, these systems could function as liquid metamaterials, offering a new platform for achieving exotic and tunable light-matter interactions.

Ultimately, the discovery of the Brownian spin-locking effect serves as a powerful reminder that complex, disordered systems continue to be a source of unexpected and powerful wave phenomena. The principles uncovered here may inspire the discovery of analogous effects in other physical systems, with profound implications for both classical and quantum regimes.

Cast of Characters

Introduction: The Playbill for a Phenomenon of Order from Chaos

In the world of physics, disordered and chaotic systems are the great equalizers. When light passes through a medium like a colloidal suspension, where countless particles jumble and dart about in random Brownian motion, the expectation is that its delicate properties will be scrambled into a featureless, unpolarized haze. This story, however, is about a profound and counter-intuitive discovery where the exact opposite happens. It is a narrative of how spatiotemporal disorder, a force typically associated with randomness, can unexpectedly give rise to a large-scale, robust, and predictable form of order. This phenomenon, the Brownian Spin-Locking Effect (BSLE), challenges our understanding of how light interacts with complex systems and reveals that chaos itself can be a key ingredient in creating structure.

To understand this scientific drama, we first introduce the cast of characters who play the principal roles in bringing this remarkable effect to life.

• The Protagonist: The Brownian Spin-Locking Effect (BSLE)

• The Stage: The Brownian Medium

• The Key Actors: The Nanoparticles and the Incident Light

• The Plot: The Two-Act Mechanism of Order from Chaos

• The Antagonist: A Frozen Snapshot of Disorder

• The Practical Epilogue: Spin-Resolved Spectroscopy

Our story begins with the protagonist, an unforeseen hero that emerges from the very heart of the chaos.

1. The Protagonist: The Brownian Spin-Locking Effect (BSLE)

The central character of our story is the Brownian Spin-Locking Effect (BSLE), an unexpected phenomenon that fundamentally alters the script of light-matter interaction in disordered systems. The appearance of this protagonist on the scientific stage is profound, as it demonstrates that macroscale order can not only survive but thrive within a thermodynamically chaotic environment—a concept that runs contrary to conventional physical intuition.

The BSLE is defined by a set of remarkable and robust attributes that distinguish it as a novel physical effect:

• Large-Scale Spin Separation: The effect manifests as the dramatic division of scattered light into two distinct regions, each containing an opposite spin (or circular polarization). This spin-split is enormous, reaching centimeter scales, making it the largest such phenomenon ever reported in disordered structures.

• Robustness in Disorder: Despite the constant, erratic motion of the nanoparticles in the Brownian system, the observed spin separation is remarkably stable. The spatial fluctuations within each spin-locked region are very small, indicating a surprisingly resilient form of order.

• Ubiquity and Universality: The BSLE is not a niche effect tied to specific conditions. It is a universal phenomenon observed for nanoparticles of different shapes, sizes, materials—including gold and Fe3O4—and across various concentrations.

The BSLE provides an entirely new experimental platform for investigating the large-scale spin behaviors of diffused light. More than just a scientific curiosity, it opens a direct path to practical applications, particularly in the field of precision metrology. To appreciate how this hero emerges, we must first examine the chaotic stage upon which it performs.

2. The Stage: The Brownian Medium

Our story unfolds on a stage seething with microscopic chaos: the Brownian medium. This environment is characterized by spatiotemporal disorder, where countless nanoparticles are driven into erratic movement by thermal fluctuations. In theory, such a dynamic and chaotic environment should be hostile to the formation of any large-scale, delicate order. The continuous, random collisions between particles and fluid molecules create an unpredictable landscape that is expected to randomize the properties of any light passing through it.

In the experiments that revealed this phenomenon, the stage consisted of a colloidal suspension of spherical gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), with an average diameter of 250 nm, suspended in water within a glass container. The defining characteristic of this stage is the incessant Brownian motion, which was measured to produce a coherence time of approximately 0.7 milliseconds for the scattered light. Because the camera’s 2-second exposure time is thousands of times longer than this 0.7-millisecond coherence time, the resulting image is an average over countless distinct, random particle configurations. This ensures that the observed order is a true feature of the thermodynamically disordered system, not an artifact of a single frozen moment.

Upon this chaotic stage, two key actors interact to create the unexpected plot twist at the heart of our story.

3. The Key Actors: The Nanoparticles and Incident Light

The emergence of the Brownian Spin-Locking Effect is driven by the interplay between two primary actors: the individual nanoparticles, which act as millions of tiny scatterers, and the incident light that illuminates them, serving as the catalyst for the entire phenomenon.

The Nanoparticles: The Seeds of Order

While the collective system is disordered, the individual nanoparticles are the fundamental sources of the spin field that ultimately creates large-scale order. The physical properties of these particles are critical to the effect. In one experiment, researchers compared the scattering from 250 nm gold nanoparticles with that from 400 nm gold nanoparticles. The result, shown in Figures 2D-G, was a complete flip in the sign of the observed spin, proving unequivocally that the phenomenon originates from the colloid itself and is highly dependent on the properties of the individual scatterers. This versatile role is further highlighted by the fact that the effect has been demonstrated with different materials, such as Fe3O4, and at various concentrations.

The Incident Light: The Catalyst

The catalyst for this phenomenon is remarkably simple: an x-polarized plane wave laser (at a wavelength of 639 nm) directed at the sample at a normal incident angle. The simplicity of this illumination is a key piece of the puzzle. Other known optical spin phenomena often rely on complex illumination, such as tilted or tightly focused beams, or are related to the transverse spin of the laser. By using a standard, normally incident plane wave, the researchers ruled out these conventional causes, demonstrating that the BSLE is an intrinsic property of the scattering process itself.

With the stage set and the actors introduced, we can now turn to the plot itself—the two-act mechanism that explains how these elements combine to produce order from chaos.

4. The Plot: The Two-Act Mechanism of Order

The physical explanation for the Brownian Spin-Locking Effect unfolds like a two-act play. The first act takes place at the microscopic level, revealing an intrinsic secret held by each individual nanoparticle. The second act scales this secret up to the macroscopic world through the collective, incoherent action of the entire crowd of particles. This elegant two-part mechanism is the key to understanding how a system defined by disorder can produce such a stunningly ordered result.

Act I: The Intrinsic Secret of a Single Particle (Spin-Orbit Interaction)

The origin of the spin effect lies in the fundamental physics of light scattering from a single, isotropic spherical nanoparticle. The scattering process itself universally breaks spin symmetry due to intrinsic spin-orbit interactions (SOIs). This means that even a simple, symmetric particle, when excited by linearly polarized light, will generate a complex spin pattern in the light it scatters.

As shown by the theoretical model in Figure 4A, a single gold nanoparticle generates a characteristic “four-lobe spin texture” in the scattered field. For very small particles in the Rayleigh limit, this spin field is evanescent, decaying rapidly as 1/r³. For the larger nanoparticles used in this experiment, however, the spin field becomes radiative, decaying much more slowly as 1/r². This crucial detail means the spin signature can propagate into the far field, survive multiple scattering events, and influence other particles. This intrinsic, predictable, and far-reaching spin pattern generated by every single particle is the seed from which the large-scale order grows.

Act II: The Power of the Crowd (Incoherent Multiple Scattering)

The crucial second act involves the collective behavior of a massive number of nanoparticles engaged in incoherent multiple scattering. Here lies the central paradox of the discovery: the thermodynamic disorder of the Brownian medium, which would normally be expected to destroy any delicate effect, instead becomes its greatest ally.

In a static or “frozen” disordered system, the fixed scattering paths would create a stable but chaotic interference pattern of random speckles, where spin signals from different particles would be cancelled out unpredictably. In the Brownian medium, however, the rapid movement of the particles averages out these destructive interference pathways. The random motion ensures the scattering is incoherent, suppressing the spin fluctuations that would otherwise scramble the signal. Instead of being destroyed, the intrinsic spin distribution generated by each nanoparticle is preserved and continuously accumulated through countless scattering events. As light diffuses through the medium, bouncing from one randomly moving particle to the next, the spin fields add up, leading to the observed macroscale regions of opposite spin. The excellent agreement between the incoherent scattering theory (Fig. 3B) and the experimental results confirms that this collective, incoherent action is the engine driving the phenomenon.

This two-act mechanism highlights the essential role of incoherence. To fully appreciate its importance, we must consider what happens when its antagonist takes the stage.

5. The Antagonist: A Frozen Snapshot of Disorder

Every compelling story needs a villain, a force that threatens to undo the hero’s work. In our narrative, that antagonist is coherence. By contrasting the observed phenomenon with what would happen in a system where the particles are disordered but static or fixed in place, the essential and constructive role of the Brownian medium’s spatiotemporal disorder becomes strikingly clear. In this context, coherence is not a force for order but a destructive agent that eliminates the very effect we seek to understand.

When researchers simulated the experiment using a coherent scattering theory—modeling a frozen snapshot of the disordered particle arrangement—the results were drastically different from the clean spin separation seen in the lab. As shown in Figure 3C, the coherent simulation produced a field of random speckles. This is the direct result of destructive interference among coherent waves scattering from fixed particle positions. This chaotic interference pattern completely overwhelms the underlying spin structure, significantly reducing and nearly eliminating the spin-locking phenomenon.

The evolution from an incoherent to a coherent system, modeled in Figure 3D, tells the full story. In a fully incoherent system like the Brownian medium, the spin-locking is strong and distinct. However, as the degree of coherence increases, the spin distributions broaden, signifying greater spin fluctuations. This destructive interference ultimately washes out the distinct regions of opposite spin, demonstrating that a static configuration of disorder is the enemy of this particular form of large-scale order.

Having vanquished its antagonist, the Brownian Spin-Locking Effect is free to move beyond the realm of pure physics and into a practical epilogue.

6. The Epilogue: From Phenomenon to Practical Tool

The story of the Brownian Spin-Locking Effect does not end with its discovery. This novel phenomenon is not merely a scientific curiosity but can be harnessed as a powerful and practical tool for precision metrology. By carrying detailed information about the nanoparticles from which it scattered, the spin-resolved light serves as a highly sensitive probe of the microscopic world.

As a proof of concept, the researchers developed a technique called spin-resolved optical spectroscopy to accurately measure the size of the Brownian nanoparticles using a simple imaging system. The method involves illuminating the sample with a broadband laser and capturing the spin-resolved spectrum, sx(λ). This experimental spectrum is then compared with theoretical spectra calculated for different particle sizes; the size that yields the highest correlation is identified as the measured value.

The results demonstrate the technique’s high degree of accuracy when benchmarked against traditional Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) measurements.

This new method, born from a fundamental discovery, holds broad potential for applications in chemistry, biology, material science, and micromechanics, offering a simple yet precise way to characterize nanoparticles.

7. The Directors: The Research Team and Future Vision

This scientific narrative was directed by a team of researchers who first read this remarkable tale from nature’s script, unveiling a new chapter in the physics of disordered systems. Their work not only explains the present phenomenon but also previews the exciting sequels to this scientific story.

Future research directions include investigating the dynamical properties of the spin effect using high-speed optical detection or by slowing the Brownian motion itself. Another intriguing possibility is to use engineered nanostructures as thermally fluctuated “meta-molecules.” This would transform the Brownian system into a “liquid metamaterial,” a novel state of matter that could enable exotic and highly customized light-matter interactions.

This discovery is a profound reminder that within the universe’s most chaotic systems may lie the simplest and most elegant forms of order, waiting for the right light to be shone upon them.

FAQ

1.0 Foundational Concepts: Understanding the Core Discovery

The Brownian Spin-Locking Effect (BSLE) represents a novel and counterintuitive discovery in the field of wave physics. It reveals how a large-scale, orderly phenomenon can emerge from a system defined by randomness and disorder. This section answers the most fundamental questions about what the effect is, what “spin-locking” means for light, and why its observation in a disordered system is scientifically significant.

1.1 What is the Brownian spin-locking effect (BSLE)?

The Brownian spin-locking effect is the large-scale separation of light’s spin components within a Brownian medium—a system defined by spatiotemporal disorder, where particles are in constant, erratic motion driven by thermal fluctuations. Imagine a laser beam entering a cloudy liquid from the right. Instead of the light just scattering randomly, the BSLE causes the cloud to split into two massive, distinct regions: the top half glowing with light spinning one way (right-handed), and the bottom half with light spinning the opposite way (left-handed). This robust, macroscale separation emerges from the collective, disordered scattering of countless individual nanoparticles.

1.2 Why is this discovery considered surprising?

This discovery is surprising because it defies the conventional expectation that strong randomness destroys delicate, coherent wave phenomena. Scientists generally assume that spin-orbit interactions (SOIs), which are responsible for separating light’s spin components, would be severely disrupted and averaged out by overwhelming disorder. The Brownian spin-locking effect shows the opposite: the strong spatiotemporal disorder from the Brownian system does not eliminate the effect but instead enables it. What’s truly astonishing is the scale of this emergent order. The experimentally observed spin-separated regions can easily reach a centimeter scale—the largest ever reported in disordered structures. This means that countless nanometer-sized particles, through their chaotic motion, collectively create a coherent, ordered optical phenomenon that is billions of times larger than themselves.

1.3 What does “spin-locking” of light mean in this context?

In optics, the “spin” of light is its intrinsic angular momentum, which is associated with its circular polarization. Light can be either right-handed or left-handed circularly polarized. In this context, “spin-locking” refers to the stable, large-scale spatial separation of these two opposite spin components into distinct regions. This separation is quantitatively characterized by the normalized spin value sx, calculated as:

sx = (IR - IL) / (IR + IL)

Here, IR and IL are the measured intensities for the right-handed and left-handed circular polarizations, respectively. A positive sx value indicates a region dominated by right-handed polarization, while a negative value indicates a region dominated by left-handed polarization.

This discovery of what gives rise to the BSLE naturally leads to the question of how this counterintuitive phenomenon is physically possible.

2.0 The Physical Mechanism: How the BSLE Works

To appreciate the robustness of the Brownian spin-locking effect, it is essential to deconstruct the complex physics into its two essential components. The phenomenon arises from a combination of a fundamental property of light scattering from a single particle and the collective, chaotic behavior of countless particles. Understanding this dual mechanism reveals how order can emerge from disorder.

2.1 What two physical processes are responsible for the BSLE?

The BSLE is driven by a two-part physical mechanism that combines a microscopic interaction with a macroscopic collective effect:

1. Intrinsic Spin-Orbit Interactions (SOI): When light scatters off an individual nanoparticle, an intrinsic interaction between the light’s spin and its orbital angular momentum universally generates radiative spin fields. This is a fundamental property of scattering and does not require any special asymmetry in the nanoparticle’s shape or material.

2. Incoherent Multiple Scattering: The erratic, random movement of the many nanoparticles in the Brownian medium leads to incoherent multiple scattering. This thermodynamic disorder is the key to preserving and accumulating the individual spin fields generated by each particle, allowing them to build up into a macroscale effect.

2.2 How does a single nanoparticle create a spin-dependent field?

When a single spherical nanoparticle is excited by linearly polarized light, the scattered radiation field becomes inherently spin-dependent when observed from a direction perpendicular to the incident light. This effect arises from out-of-phase couplings between different harmonic modes of the scattered light, such as the electric dipole, magnetic dipole, and electric quadrupole modes, as described by Mie scattering theory. This coupling creates a characteristic “four-lobe” spin texture in the space surrounding the particle. This means that light scattered in certain directions will have a “spin-up” state (e.g., right-handed circular polarization), while light scattered in other directions will have a “spin-down” state. Crucially, this spin-separating effect happens even with perfectly simple, spherical nanoparticles. It’s a universal property of light scattering itself, not a quirk of using specially shaped particles.

2.3 What is the critical role of Brownian motion and incoherence?

The Brownian motion of the nanoparticles is critical because it ensures the scattering is incoherent. In a static, “frozen” disordered system, the light waves scattered from fixed particles interfere with each other, creating a complex and random “speckle” pattern—much like the shimmering, grainy pattern of a laser pointer on a rough wall. This chaotic interference completely scrambles the delicate spin information from each particle, eliminating any large-scale effect.

In contrast, the constant, erratic movement of particles in a Brownian system averages out these interference effects. This thermodynamic disorder effectively preserves the fundamental four-lobe spin distribution from each individual nanoparticle. Through multiple incoherent scatterings, these individual spin fields are constantly accumulated, leading to the formation of the two large, distinct regions of opposite spin.

The theoretical mechanism provides a compelling explanation, which is powerfully substantiated by direct experimental evidence.

3.0 Experimental Observation and Validation

Robust scientific claims require rigorous experimental proof and theoretical validation. The existence of the Brownian spin-locking effect was not only predicted by theory but also clearly observed in a laboratory setting. This section details the experimental setup used to discover the effect and shows how the resulting data provides strong evidence for the proposed incoherent scattering theory.

3.1 What was the experimental setup used to observe the effect?

The experiment used a straightforward optical setup to observe light scattered from a colloidal suspension. The key components were:

• Light Source: An x-polarized plane wave laser with a wavelength of 639 nm.

• Sample: A glass container holding a suspension of spherical gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) in water.

• Observation: A camera system with a lens, positioned to capture images of the scattered light at an angle perpendicular to the laser’s path.

• Spin Detection: A set of optical filters (a quarter-wave plate and a linear polarizer) placed before the camera, which allows the researchers to isolate and measure the intensity of just the right-handed circularly polarized light (IR) and then, separately, the left-handed light (IL).

3.2 What were the definitive experimental results?

The experimental results provided clear and definitive evidence of the BSLE.

First, using 250 nm gold nanoparticles, the researchers observed that the scattered light formed a central “ballistic region” (overlapping with the direct laser path) and two large “diffusion regions” on opposite sides. When the spin was measured, these two diffusion regions showed distinct, opposite spin angular momenta, with one region being predominantly right-handed polarized and the other left-handed.

Second, and crucially, they repeated the experiment with a different sample of 400 nm gold nanoparticles. This resulted in the same spatial separation of spin, but the sign of the spin in each region was flipped. This demonstrated that the effect is not an artifact of the optical setup but is intrinsically linked to the physical properties of the scattering nanoparticles. This fundamental link to particle properties was further confirmed in other experiments using nanoparticles of different materials and concentrations, proving the effect is a general phenomenon.

3.3 How does the incoherent scattering theory match the experimental data?

The experimental data aligns remarkably well with the predictions of the incoherent scattering theory. When the spatial distributions of intensity and spin were calculated using this theory, the results showed “excellent agreement” with the experimental observations. The statistical properties of the measured light, such as the probability distribution of intensity and spin values, were also accurately reproduced by the theory.

In contrast, a simulation based on a coherent scattering theory—which assumes the nanoparticles are static—produced a drastically different result. The coherent model predicted an image full of random speckles and a significantly reduced spin-locking effect. This mismatch strongly validates the conclusion that incoherence, driven by Brownian motion, is the essential ingredient for producing the observed large-scale spin-locking.

Having been experimentally confirmed, this fundamental discovery opens the door to new technologies and applications.

4.0 Applications and Broader Implications

The translation of fundamental scientific discoveries into practical technologies is a critical driver of progress. The Brownian spin-locking effect is more than a scientific curiosity; it provides a new way to probe and measure the properties of nanoparticles. This section explores the “so what?” of the BSLE, detailing a proof-of-concept application in metrology and discussing the broader implications for science and engineering.

4.1 What is a practical application of the BSLE?

A direct practical application of the BSLE is a new technique called spin-resolved optical spectroscopy, designed for accurately measuring the size of nanoparticles. The method works by illuminating the Brownian sample with a broadband laser source. The scattered light is collected, and its spin spectrum—the normalized spin value sx as a function of wavelength λ—is measured. This experimental spectrum, sx(λ), is then compared to a pre-calculated library of theoretical spectra for nanoparticles of different sizes. The particle size that produces a theoretical spectrum with the highest correlation to the measured one is identified as the size of the nanoparticles in the sample.

4.2 How accurate is this new measurement technique?

A proof-of-demonstration experiment showed the technique to be highly accurate. Three different samples of gold nanoparticles were measured using both the spin-resolved spectroscopy method and a benchmark technique (Scanning Electron Microscope, or SEM). The results, summarized below, show excellent agreement.

These results demonstrate that the BSLE-based method can determine nanoparticle size with high precision, offering a new tool for materials characterization.

4.3 What are the future scientific directions for this research?

The discovery of the BSLE opens up several exciting avenues for future research and technological development, as outlined in the discussion of the findings:

• Precision Metrology: The spin-resolved method could be further developed into a versatile tool for broad applications in chemistry, biology, and material science, enabling the detection of not just size but also material composition and other properties of nanoparticles.

• Dynamic Effects: By using faster optical detection systems or by controlling the sample’s temperature or viscosity to slow down the Brownian motion, researchers could investigate the dynamic evolution of these spin effects over time.

• Liquid Metamaterials: The principle can be extended by using engineered nanostructures with customized shapes and properties. In this vision, the nanoparticles act as “thermally fluctuated meta-molecules.” In essence, the entire disordered liquid could be engineered to behave as a new type of ‘smart fluid’ that manipulates light in ways not possible with conventional materials.

Ultimately, this discovery serves as an inspiration for finding analogous phenomena where order emerges from disorder in other complex, wave-based systems, from classical acoustics to quantum mechanics.

Table of Contents with Timestamps

Introduction: The Paradox of Chaos and Order | 00:00 Opening meditation on disorder in physics and the unexpected discovery that challenges fundamental assumptions about thermal chaos and light.

Brownian Motion: The Foundation of Disorder | 03:48 Historical context and physics of Brownian motion, from Einstein’s 1905 work to modern applications in dynamic light scattering.

The Brownian Spin-Locking Effect Discovery | 07:37 Introduction to the international research collaboration and the core paradox: how spatiotemporal chaos preserves and amplifies light’s spin angular momentum.

Experimental Setup and Initial Findings | 12:12 Description of the remarkably simple experimental apparatus and the stunning macroscale spin separation observed in chaotic gold nanoparticle suspensions.

Universality Through Control Experiments | 17:14 Validation tests demonstrating material independence, particle size effects, and robustness at extreme concentrations.

The Mechanism: How Chaos Enables Order | 20:24 Two-part theoretical framework explaining intrinsic spin-orbit interaction and the role of incoherent multiple scattering.

Coherent Versus Incoherent Systems | 22:33 Comparative analysis of why static systems destroy spin signals while temporal chaos preserves them through decoherence.

Mie Scattering and Multipole Physics | 26:10 Deep dive into the electromagnetic theory underlying single-particle scattering and the generation of radiative spin fields.

Near-Field Versus Far-Field Spin | 27:58 Explanation of why particle size determines whether spin remains trapped or propagates through the medium.

Geometric Phase and Natural Symmetry Breaking | 32:21 Connection to fundamental physics concepts and the elegant emergence of geometric phase from scattering geometry.

Practical Applications: Spin-Resolved Optical Spectroscopy | 33:54 Development of a new precision measurement tool for nanoparticle characterization with 89-99% accuracy.

Future Horizons and Liquid Metamaterials | 40:41 Visionary implications for dynamic optical systems, quantum applications, and the paradigm shift in understanding randomness.

Closing Reflection: Chaos as Filter | 42:29 Final thoughts on how thermal disorder reveals hidden order and the universal implications for science and measurement.

Index with Timestamps

Anderson localization, 08:08

Angular momentum, 01:08, 08:49, 30:42

Asymmetry, 11:25, 11:51

Ballistic region, 16:37, 19:34, 24:46

Beta distributions, 25:52

Bo Wang, 02:10, 09:43, 20:33

Brownian motion, 00:38, 03:48, 04:01, 21:28, 39:29

Camera exposure, 06:52, 25:08

Chaos, 00:25, 07:26, 21:22, 26:04, 40:01

Chen, Pei Yen, 01:53

Chen, Shanfeng, 02:02

Circular polarization, 10:30, 16:12, 27:40

Coherence, 01:21, 07:15, 22:20, 25:45

Coherence time, 06:38, 22:51, 25:16

Concentration, 19:16, 37:35, 42:00

Decoherence, 23:19

Depolarization, 01:26, 37:29

Destructive interference, 09:15, 23:04, 25:45

Diffusion, 05:28, 18:32, 35:23

Diffusion region, 15:11, 24:04, 35:34

Dynamic light scattering, 05:29, 36:25

Electric dipole, 27:05, 28:21, 30:13

Electric field, 10:23, 33:03

Electromagnetic, 18:32, 26:27, 32:12

Erez Hasman, 01:53

Evanescent field, 28:34

Far-field, 28:07, 31:29, 32:02

Geometric phase, 32:25, 33:10, 33:54

Gold nanoparticles, 04:01, 17:41, 30:00, 31:52

Hasman, Erez, 01:53

Huygens dipole, 31:43

Hydrodynamic diameter, 05:40, 36:28, 39:09

Incoherent scattering, 07:16, 20:00, 21:27, 24:47

Interference, 09:15, 23:04, 25:45

Janus dipole, 30:54, 31:15

Li, Mei, 01:53

Linear polarization, 13:00, 14:27, 27:40

Macroscale, 02:26, 14:18, 18:13, 29:55, 34:15

Magnetic dipole, 27:05, 29:20, 30:13

Metamaterial, 41:43

Metrology, 03:23, 34:09, 38:14

Metasurfaces, 11:35

Mie scattering, 26:27, 27:31, 35:15

Multipole, 26:26, 29:19, 30:36, 41:31