With every article and podcast episode, we provide comprehensive study materials: References, Executive Summary, Briefing Document, Quiz, Essay Questions, Glossary, Timeline, Cast, FAQ, Table of Contents, Index, Polls, 3k Image, and Fact Check.

We've got freedom all wrong.

For decades, Americans have embraced a dangerously narrow definition of liberty – one that Timothy Snyder, in his penetrating book "On Freedom," calls "negative freedom." It's the freedom from interference, from rules, from being told what to do. It's about being left alone.

And it's making us more vulnerable than we realize.

The Empty Promise of Negative Freedom

There's something uniquely American about our obsession with this kind of freedom. We celebrate the rugged individual, disconnected from community obligations. We valorize the entrepreneur who "disrupts" established systems. We've built an entire political identity around suspicion of governance itself.

"Don't tread on me" isn't just a historical flag – it's practically our national mantra.

But while we've been busy declaring our independence from each other, something insidious has happened. The vacuum created by this narrow vision of freedom – this absence of connections, obligations, and shared truths – has been systematically filled by forces that ultimately restrict our actual freedom.

Monopolies. Propaganda. Weaponized social media. Oligarchic wealth concentration.

Sound familiar? It should.

The Russian Warning We Ignored

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Americans largely interpreted it as a simple victory for capitalism and our brand of negative freedom. Just remove the state controls, we thought, and democracy and markets would naturally flourish.

History had other plans.

What actually emerged in Russia wasn't a flourishing democracy but an oligarchy – one that eventually consolidated under Putin's authoritarian control. The warning signs were there for decades before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, but our narrow conception of freedom blinded us to the danger.

Here's the uncomfortable parallel Snyder draws: the same forces that hollowed out Russian society – monopoly capitalism, propaganda designed not to convince but to confuse, the systematic undermining of truth itself – are actively working in America right now.

And our fetishized notion of negative freedom makes us uniquely vulnerable to them.

The Body Problem

To understand why negative freedom fails us so completely, Snyder introduces a crucial philosophical distinction borrowed from German thought – the difference between Körper and Leib.

Körper is the body as object, the physical thing a doctor might examine.

Leib is the body as subject, as lived experience – the center of your feelings, intentions, and inner world.

Our obsession with negative freedom recognizes only the Körper – it sees human beings as objects to be unrestrained, not subjects with inner lives and connections to others. It misses the entire dimension of our subjective experience.

This explains why Americans can simultaneously celebrate "freedom" while tolerating systemic failures in healthcare, education, and basic social support. We've constructed a vision of liberty that sees restrictions on physical movement as tyranny but doesn't register the profound unfreedom of preventable suffering.

Snyder's appendix story is telling – when the medical system treated his body purely as Körper, as an object potentially generating profit rather than the seat of a person's suffering, it nearly killed him.

Sound familiar? It's the same mentality that leads us to measure success by GDP growth while ignoring skyrocketing rates of depression, addiction, and social isolation.

The Ukrainian Alternative

While Americans have been perfecting our negative freedom, Ukrainians facing Russian invasion have demonstrated something far more powerful – what Snyder calls positive freedom.

When Ukrainians talked about what they were fighting for, it wasn't just freedom from Russian control. It was freedom forsomething – the ability to shape their own future, to build the society they wanted, to see their children smile again.

Their resistance wasn't just physical but existential – a refusal to let their collective identity be erased. And what made the difference wasn't just weapons but their recognition of each other's full humanity – their Leib, not just their Körper.

This is positive freedom in action – the freedom that comes from engagement, not isolation; from connection, not just from being left alone.

The Path Forward: From "Freedom From" to "Freedom For"

Our concept of freedom needs an urgent upgrade if we hope to resist the forces undermining it. Here's what that might look like:

First, recognize that true freedom is active, not passive. It's not something handed down by founding fathers or automatically guaranteed by markets. Freedom requires ongoing participation and mutual recognition of each other's full humanity.

Second, understand that empathy isn't optional for freedom – it's essential. Thinkers like Edith Stein and Simone Weil emphasized that truly seeing others, even across differences, is fundamental to a free society. When we recognize others' subjective experiences, we gain a more complete picture of reality rather than just seeing people as obstacles or tools in our personal worlds.

Third, acknowledge that practicing skills and values creates its own form of liberation. Think about the difference between awkwardly learning an instrument and the freedom found in playing it skillfully without conscious effort. Freedom isn't just about removing constraints but about developing capabilities.

Finally, reconnect freedom to values. Edith Stein described a "world of values" beyond physical reality – purposes and meanings that give direction to our choices. Our intentional actions based on values like justice, creativity, or kindness create pathways between that ideal world and our concrete reality.

The Freedom We Actually Need

The most dangerous aspect of our negative freedom obsession is how it blinds us to emerging threats. If you believe freedom is just the absence of rules, you might not recognize the danger when someone starts filling that void with lies, spectacle, and ultimately unchecked power.

America's confidence in its exceptional freedom, our belief that "it can't happen here," might actually make us more vulnerable to the very forces that have undermined freedom elsewhere.

True freedom isn't just removing chains. It's actively engaging with others, recognizing their full humanity, and working collectively to create the conditions where everyone can flourish.

In an age of weaponized social media, climate crisis, and democratic backsliding, perhaps we need fewer "don't tread on me" flags and more recognition that my freedom is bound up in yours – that we're all subjects, not just objects, in this shared project of democracy.

Our survival might depend on it.

If you found this perspective valuable, please consider subscribing and sharing with others. The defense of meaningful freedom requires exactly the kind of engaged community we've been told to avoid.

Link References

Episode Links

Youtube

Other Links to Heliox Podcast

YouTube

Substack

Podcast Providers

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Patreon

FaceBook Group

STUDY MATERIALS

Briefing Document

I. Executive Summary

The provided excerpts from Timothy Snyder's "On Freedom" explore a multifaceted understanding of freedom, moving beyond conventional definitions of absence or negative liberty. Snyder argues that true freedom is a positive presence, requiring active engagement with oneself, others, and the world of values. He introduces the concept of Leib (the living, feeling body) as crucial to self-knowledge and empathy, which are foundational for sovereignty. The book critiques ideologies that restrict freedom, particularly fascism and certain forms of Marxism, which deny individual agency and the richness of human experience. Snyder emphasizes that freedom is not a solitary pursuit but is realized in community and across generations, requiring conscious effort and a willingness to engage with the "world of values" – a realm of multiple, sometimes conflicting, virtues. He uses personal anecdotes, historical examples, and philosophical concepts to illustrate these ideas, highlighting the importance of unpredictability, mobility, solidarity, and truth in the pursuit and maintenance of freedom. The text is presented as a series of reflections, framed by personal experiences, particularly in the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine.

II. Key Themes and Ideas

Freedom as a Positive Presence: Snyder challenges the notion of freedom as simply the absence of constraints (negative freedom). Instead, he defines it as a positive presence, a "life in which we choose multiple commitments and realize combinations of them in the world." It is the "condition in which all the good things can flow within us and among us."

Quote: "Freedom is not an absence but a presence, a life in which we choose multiple commitments and realize combinations of them in the world."

Quote: "This is not because freedom is the one good thing to which all others must bow. It is because freedom is the condition in which all the good things can flow within us and among us."

Snyder explicitly contrasts his view with the philosophical concept of "negative freedom," arguing that it is "empty without some idea of positive liberty."

The Importance of the Leib (Living Body): Drawing on the work of Edith Stein, Snyder introduces the distinction between Körper (body as a physical object) and Leib (the living, subjective body). Understanding oneself and others as Leib is fundamental to freedom.

Quote: "The first form of freedom, as I hope to show, is sovereignty. A sovereign person knows themselves and the world sufficiently to make judgments about values and to realize those judgments."

Quote: "For Stein, we gain knowledge of ourselves when we acknowledge others. Only when we recognize that other people are in the same predicament as we are, live as bodies as we do, can we take seriously how they see us."

Quote: "The word Leib designates a living human body, or an animal body, or the body of an imaginary creature in a story... A Leib can move, a Leib can feel, and a Leib has its own center... We can always see some of our Leib, but we can never see all of it."

Understanding others as Leib fosters empathy and allows us to see the world differently, preventing us from seeing ourselves as isolated individuals "outside the world, or against the world."

Sovereignty as Self-Knowledge and Realization of Values: Sovereignty, for Snyder, is the capacity to make judgments about values and realize those judgments in the world. This requires self-knowledge, which is gained through recognizing the Leib of others.

Quote: "The first form of freedom, as I hope to show, is sovereignty. A sovereign person knows themselves and the world sufficiently to make judgments about values and to realize those judgments."

Quote: "Knowing me and knowing his sister, he immediately knew what I meant, and then he could also see that this is objective knowledge, of the kind we cannot get alone."

He uses the analogy of pitching in baseball to illustrate this: visualizing a pitch and then bringing it to reality is a small act of sovereignty, grounded in the "world of values."

Quote: "In a visualization of this sort, which Stein called 'an intention permeating the whole,' another world appears, a beat ahead of this one... In this humble way, I am sovereign."

The "World of Values" (The Fifth Dimension): Snyder describes a realm of good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, distinct from the physical world (the first four dimensions of space and time). This "world of values" operates by its own rules and is a source of unpredictability and freedom.

Quote: "A sovereign person, in making choices, is acting not only within the physical world, but in a realm of good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice. That zone, which Stein called “the world of values,” is not an extension of the world of things. It is a kind of fifth dimension, with its own rules, and as such a reservoir of unpredictability for our own world of four dimensions, of space and time."

He outlines the "geometry of the fifth dimension": difference (distinct from the physical world), plurality (many virtues), and intransitivity (virtues are not reducible or rankable).

Quote: "The first rule is difference: the world of what is (the first four dimensions) and what ought to be (the fifth) are distinct. They can be brought together only through us, through our bodies. The second is plurality. In the realm of what should be are many virtues, not one. The third rule is intransitivity. The various goods are good for various reasons. The virtues are not reducible to one another. They cannot be ranked."

Unpredictability as a Hallmark of Freedom: Sovereign individuals making choices in the "world of values" introduce unpredictability into the physical world. This shared unpredictability is a sign of a free society.

Quote: "When people are sovereign together, they generate unpredictability. As they do so, they recognize this in one another, welcome it, and gain from it."

Snyder links this to Havel's idea of "normal dissidents" who are simply being themselves, living their truths and acting according to virtues, which makes them unpredictable to an oppressive regime.

He contrasts this with ideologies like Marxism and fascism that seek to eliminate unpredictability.

Critiques of Ideologies Restricting Freedom:

Fascism (Nazi Germany): Snyder highlights how Hitler's ideology denied the Leib of others, viewing certain groups as "foreign bodies" (Fremdkörper) infesting the "racial body" (Volkskörper). This dehumanization paved the way for genocide. Hitler also denied the "world of values" and the future, leading to a politics of pure force and domination based on a distorted view of nature and race.

Quote: "Hitler took a view of the human body utterly opposed to Stein’s. In Mein Kampf, he wrote of Fremdkörper, “foreign bodies,” infesting the Volkskörper, the German racial organism. Rather than seeing each person in Germany as a distinct human body, Nazis portrayed the German race as a single organism and the Jews as the foreign objects, bacteria or parasites."

Quote: "Stripped of the fifth and the fourth, the first three dimensions are left barren and tragic. When Hitler spoke of “living space” for Germans, he meant killing space for others."

Certain Forms of Marxism and Stalinism: Snyder suggests that while Marx offered valuable analysis, his solution depended on the idea of a single human nature, limiting the "world of values" to a single ideal (communism) and creating a predetermined future. Stalinism further restricted freedom by concentrating power and denying individual agency.

Quote: "Although Marx’s analysis of capitalism was valuable, his proposed solution depended on the assumption that there was a single human nature to which we would return... In Marx’s view of the world, private property was a singular evil, and its abolition would restore to each person that lost essence."

Quote: "In Stalinism, there was a future, a glimmer of the fourth dimension, but it was a single future, defined by the few. There was a hint of the fifth dimension, but it was the single value of communism, jealously crowding out all the others."

Freedom in Community and Across Generations: While freedom is an individual quality, it is nurtured and sustained by a community. We learn about ourselves and the world through others and our past. Freedom is also a legacy passed down through generations.

Quote: "Only an individual can be free, but only a community can make individuals. And yet for a community to do this, generation upon generation, its practices must be examined in light of the demands of freedom."

He reflects on the historical context of his own life and the places he has lived (Ohio farm, Vienna, Ukraine) to illustrate how personal history is intertwined with larger historical forces and the actions of previous generations.

Mobility as a Component of Freedom: Snyder discusses different forms of mobility (social, physical) and how they relate to freedom. He contrasts imperial and colonial forms of mobility with the mobility that allows individuals to pursue better futures and connect with others.

He links mass incarceration and racial policy in the US to restricted mobility for certain groups.

He contrasts Hitler's concept of Lebensraum (living space gained through conquest and murder) with a positive understanding of mobility.

He touches on the freedom of movement in post-Soviet Ukraine and the desire for European integration as a symbol of freedom.

Truth and Factuality: Snyder connects freedom to truth and factuality, particularly in the context of political manipulation and propaganda. He argues that denying the existence of a nation or distorting history (as Putin does with Ukraine) is a form of action that restricts freedom and enables violence.

Quote: "When a dictator denies the existence of a nation, this is genocidal hate speech, a form of action that must be resisted."

He implicitly links the ability to "live in truth" (a concept associated with Havel) to maintaining a free society.

The Role of Government and Institutions: While acknowledging the limitations of government, Snyder suggests that government can play a role in enabling freedom, particularly by addressing issues like mass incarceration, ensuring fair voting access, and providing necessary infrastructure and support for individuals (e.g., for childbirth). He distinguishes this from the fascist idea of the state as the ultimate sovereign or Marxist ideas of a predetermined social order.

III. Most Important Ideas/Facts

Freedom is a positive state, not just an absence of constraint.

Understanding ourselves and others as Leib (living bodies) is essential for self-knowledge, empathy, and therefore sovereignty.

Sovereignty involves the capacity to make choices based on values and realize those choices in the world.

The "world of values" is a distinct realm of virtues (plural and non-reducible) that is a source of unpredictability and freedom.

Unpredictability is a characteristic of free individuals and societies.

Ideologies like fascism and certain forms of Marxism restrict freedom by denying individual agency, the "world of values," or a plural future.

Freedom is not a solitary pursuit; it requires community and is passed down through generations.

Mobility (social and physical) is connected to freedom, and restricting it is a form of unfreedom.

Truth and factuality are crucial for maintaining freedom, and denying them is a form of harmful action.

The experiences in Ukraine (past and present) serve as a significant backdrop and illustration of the struggle for freedom against oppressive forces.

IV. Supporting Quotes

"Liberty begins with de-occupying our minds from the wrong ideas. And there are right and wrong ideas."

"Freedom is the absolute among absolutes, the value of values."

"When we identify with them as they regard us, we understand ourselves as we otherwise might not. Our own objectivity, in other words, depends on the subjectivity of others."

"A little leap of empathy is at the beginning of the knowledge we need for freedom."

"Your Leib pushes back into the world, changing it. It translates physics into pain and pleasure, chemistry into desire and disappointment, biology into poetry and prose. It is the permeable membrane between necessity and freedom."

"If I do not exist as a Leib because the existence of my group is denied, I can be subjected to genocide."

"The limits of a Leib are its capabilities."

"Any single virtue has an absolute claim on us, but we can never realize it absolutely, not least because it clashes with other virtues."

"Each of us enchants the world unpredictably or not at all."

"The choices of each sovereign person will be in a unique combination, grounded in a unique set of commitments."

"Necessity is the mother of invention; the better we understand necessity, the more inventive we are. As we choose over time, working from the law of necessity to the law of freedom, we invent ourselves."

"He thought the 'dissidents' were just being themselves, living their truths, sovereign and unpredictable." (referring to Havel)

"Only an individual can be free, but only a community can make individuals."

"When a dictator denies the existence of a nation, this is genocidal hate speech, a form of action that must be resisted."

"Our universe is a play of matter and energy, back and forth. Life is a special form of that play. We are a special form of life, capable of freedom because we are capable of seeing our own purposes and realizing them."

"Democracy is the system toward which the forms of freedom lead, the best resolution of freedom as a principle."

V. Context and Significance

The excerpts are framed by Snyder's experiences, including his childhood on an Ohio farm, his academic career, and his time in Central and Eastern Europe, particularly Ukraine. The war in Ukraine serves as a constant, tangible backdrop, illustrating the fragility of freedom and the real-world consequences of denying the existence and sovereignty of others. The journey by train from Kyiv to the Polish border mentioned at the beginning underscores the contemporary relevance and urgency of his reflections on freedom. The inclusion of diverse historical figures and concepts (Edith Stein, Václav Havel, Leszek Kołakowski, Carl Schmitt, Hitler, Marx, etc.) provides a rich intellectual framework for his arguments. The personal anecdotes, such as teaching a prison seminar and playing catch with his daughter, ground the abstract philosophical ideas in concrete human experience.

Quiz & Answer Key

Quiz

According to the text, what is the fundamental nature of freedom, and why is it considered the "value of values"? Freedom is not an absence but a presence, a life of chosen commitments. It's the "value of values" because it's the condition enabling all other good things to flow within and among us.

Explain Edith Stein's distinction between Körper and Leib. How does understanding Leib contribute to our knowledge of ourselves and the world? Körper is a physical body, subject to physical laws (like a corpse or foreign body). Leib is a living, feeling body with its own center ("zero point"). Understanding Leib in ourselves and others allows for empathy and objectivity, revealing the world beyond our isolated perception.

How does the parable of the Good Samaritan illustrate the concept of freedom as presented in the text? The Samaritan in the story is free because he acts according to his own values (compassion) and realizes them by helping the injured Jew. Despite physical constraints (gravity, inertia), he chooses to stop and assist, demonstrating a sovereign act.

What is the significance of the "world of values" as described by Stein and Kołakowski? The world of values is a realm of good and evil, right and wrong, distinct from the physical world. It has its own rules, is characterized by plurality and intransitivity (virtues cannot be ranked), and serves as a source of unpredictability for our four-dimensional world.

How does the author connect his experience pitching baseball to the concept of sovereignty? Pitching involves visualizing a desired outcome and attempting to bring it into reality, a process Stein called "an intention permeating the whole." The pitcher, working between the physical world ("lump of physics") and the world of values (intentions, thoughts about the future), makes small passages between them, demonstrating a humble form of sovereignty.

Explain how the experience of the Borderlanders artists in Sejny, Poland, performing music in a former synagogue, relates to the idea of freedom. The Borderlanders use art to connect with others and the past, enhancing their sovereignty through a new capacity (playing music). Their performance in the former synagogue, playing Jewish music, allows the history and presence of the murdered Jewish community to exist in some way, demonstrating a connection to a world of values that transcends physical absence.

What is the fascist notion of sovereignty according to Carl Schmitt, and why does the author dismiss it as "puerile"? Schmitt argued that true sovereignty lies in making an exception to the rules. The author dismisses this as "puerile" because it is merely a statement about power based on rule-breaking, lacking a substantive understanding of what sovereignty means or ought to mean, and neglecting the needs of actual children for support and upbringing.

How does the author use the concept of Leib to argue for societal accommodations for childbirth? Acknowledging the Leib of women means recognizing the unique burden and decision-making involved in childbirth. Providing societal accommodations removes a source of unfreedom for women and increases the likelihood that children can grow up free, as freedom requires positive support, not just the absence of barriers.

What is the significance of Ukraine opening its archives after the end of the USSR? How did this contribute to understanding the Soviet Union? Ukraine keeping its archives open after 1991 was a seemingly small act with significant consequences. This fact allowed historians to learn much about the Soviet Union that was previously hidden, highlighting the importance of transparency and access to information for understanding the past.

Describe the author's interpretation of the tree rings on the old sycamore tree on his childhood farm. How do they function as "little signs from other lives"? Each tree ring represents a year of the tree's growth and survival, recording its accommodation to seasonal challenges. Like fossils or arrowheads, these rings are "little signs from other lives" that help us understand the past and our own place in time, connecting individual lives to larger histories and natural processes.

Essay Questions

Analyze the relationship between "living in truth" and unpredictability as presented in the text. How do individuals who live authentically contribute to a less predictable and potentially freer society?

Discuss the author's critique of different forms of unfreedom (e.g., negative freedom, fascist sovereignty, Stalinism, racial unfreedom, modern digital manipulation) and how his concept of freedom, rooted in Leib and the world of values, offers a counterpoint to these constraints.

Explore the role of community and intergenerational connection in the development and maintenance of individual freedom, drawing on examples from the text such as the baseball anecdote, the ringing of the bell, and the discussion of upbringing.

Examine the "geometry of the fifth dimension" and its three rules (difference, plurality, and intransitivity). How does understanding these rules help us navigate the complexities of the world of values and its relationship to the physical world?

Evaluate the author's argument that democracy is the political system best aligned with the development and expression of individual freedom and sovereignty. Consider the challenges to democracy discussed in the text, such as gerrymandering and the influence of oligarchs and brain hacks.

Glossary of Key Terms

Freedom: A presence, a life in which individuals choose multiple commitments and realize them in the world; the condition in which good things can flow.

Körper: A German term for a physical body, which may or may not be alive and is subject to physical laws.

Leib: A German term for a living human or animal body, which can move, feel, and has its own internal center or "zero point."

Sovereignty: A state or quality of being autonomous; knowing oneself and the world sufficiently to make judgments about values and realize those judgments.

World of Values: A realm of good and evil, right and wrong, and virtues, distinct from the physical world of things (the first four dimensions); the fifth dimension.

Empathy: The ability to understand and share the feelings of another; crucial for recognizing others as Leib and gaining objective knowledge of the world and oneself.

Unpredictability: A quality of sovereign individuals and societies where choices are not predetermined but arise from unique combinations of circumstances and values, interacting between the world of things and the world of values.

Habitude (Practice): Repeated actions or customs that shape individuals and contribute to sovereignty and the ability to realize values.

Necessity: The constraints and physical laws of the universe that individuals face.

Law of Freedom: The capacity to turn the restraints of necessity into opportunities through choice and action.

Law of Necessity: The physical laws and constraints that govern the material world.

Negative Freedom: Freedom understood as the absence of barriers or interference. The author argues this is an insufficient definition.

Positive Freedom: Freedom understood as a presence, a capacity, or a state of being where individuals can realize their purposes and values. The author emphasizes this aspect.

Living in Truth: A concept, particularly associated with Václav Havel, of living authentically according to one's values and conscience, even in the face of oppressive systems.

Dissidence: The act of nonconformity or resistance to prevailing norms or authorities, often by simply living authentically or "in truth."

Geometry of the Fifth Dimension: The structure and rules of the world of values, characterized by difference (from the physical world), plurality (of virtues), and intransitivity (virtues cannot be ranked).

Solidarity: A sense of unity or agreement among individuals, particularly based on common interests, sympathies, or purposes; crucial for creating communities that support freedom.

Mobility: The capacity to move and change, both physically (social mobility) and in terms of possibility and purpose (interaction with time and values).

Politics of Eternity: A political approach that focuses on a mythical, unchanging past, denying the possibility of a different future and hindering mobility.

Politics of Inevitability: A political approach that claims a predetermined future, often based on perceived natural laws or historical destiny, thereby suppressing unpredictability and choice.

Brain Hacks: Psychological or technological manipulations that exploit human tendencies and limit genuine thought and unpredictable action, often associated with modern technology and information environments.

Democracy: A system of government seen by the author as the political resolution that best accommodates and fosters individual freedom and sovereignty, particularly through the unpredictable actions of sovereign citizens.

Timeline of Main Events

Mid-1970s: Timothy Snyder, as a young boy, is living on an Ohio farm, playing baseball, ringing a bell by the farmhouse, and attending first grade. He experiences freedom through childhood activities.

1975: The Helsinki Final Act is signed.

1976 (Summer): Snyder, at age six going on seven, is on an Ohio farm, the setting for his reflections on childhood freedom. This is also the year the US celebrates its bicentennial, though Snyder notes the country is moving towards mass incarceration as racial policy.

1976: Around the same time as Snyder's childhood experiences, the Plastic People of the Universe are arrested in Czechoslovakia, and Michael Stipe discovers a Velvet Underground album, which inspires the formation of R.E.M. later.

1980s (Early): Snyder plays baseball as a pitcher, connecting the act of pitching to declaring freedom.

1984: Timothy Snyder's youngest brother discovers R.E.M.

1985: Timothy Snyder and his brother excitedly buy R.E.M.'s album Fables of the Reconstruction.

1989: As communism ends in Poland, the White Synagogue of Sejny is taken over by the Borderlanders, a troupe of artists and musicians who believe in using art for freedom.

1991 (August 1): President George H.W. Bush visits Kyiv and urges Ukrainians not to declare independence.

1991 (August 18): A coup attempt against Gorbachev begins, leading to the end of the USSR. Snyder, who had just celebrated his twenty-second birthday, is awakened by a Russian friend with the news.

1991 (August 24): Ukrainian communists declare the independence of their republic.

1991 (September): Snyder finishes his study of Soviet monopoly and begins graduate study in history at Oxford.

1991 (December): The formal dissolution of the USSR occurs while Snyder is in Czechoslovakia.

Early 1992 (Right after New Year’s): Snyder takes the night train from Prague to Warsaw.

1992 (April): Snyder presents a paper on Soviet monopoly in Vienna; economists from the former USSR now represent independent states.

2000s: Ukrainian citizens establish a functioning democratic system by protesting for freedom of speech and fair vote counting. Most Ukrainians begin to view the European Union as their political future.

2016 (Spring): Adam Michnik visits Yale University as a fellow.

2021 (Summer): Snyder and his daughter play catch near the White Synagogue of Sejny and observe saxophonists practicing inside.

2021: Vladimir Putin publishes an imperialist essay claiming that tenth-century events predetermined the unity of Ukraine and Russia.

Early 2022: The second Russian invasion of Ukraine begins, which Snyder references as the "second Russian invasion." This is a period of significant unfreedom, characterized by attempts to destroy Ukraine's culture and agriculture.

September 10, 2023 (6:10 a.m.): Timothy Snyder is on the Kyiv-Dorohusk train, in Wagon 10, Compartment 9, as he begins his reflection on freedom for the book.

Year preceding the book's writing: Men and women die in Ukraine so that people can move freely on the land, potentially including women warriors, a phenomenon Snyder compares to ancient Scythians.

Cast Of Characters

Timothy Snyder (T.S.): The author and narrator of the excerpts. He is a historian and professor at Yale University and the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. His reflections on freedom are deeply personal, drawing on his childhood, academic studies, experiences in Eastern Europe (particularly Ukraine), and interactions with students and historical figures.

Snyder's Daughter: Mentioned in the text as a young girl with whom Snyder plays catch and who has also become a softball pitcher. Her reactions and experiences inform Snyder's understanding of knowledge gained through interacting with others.

Snyder's Son: Mentioned as having questioned the argument of the book, leading Snyder to an example about understanding oneself through others' behavior.

Snyder's Youngest Brother: Mentioned for discovering the band R.E.M.

Snyder's Grandfather: His sentimentality about a bell on their Ohio farm contributes to Snyder's own understanding of its significance and the intergenerational nature of freedom.

George H.W. Bush: President of the United States who visited Kyiv in August 1991 and advised against Ukrainian independence.

Mikhail Gorbachev: Leader of the Soviet Union during the coup attempt in August 1991 that marked the beginning of the USSR's dissolution.

Edith Stein: A German philosopher whose work on empathy (Einfühlung) and the distinction between Körper (body as object) and Leib (living human body with subjective experience) is central to Snyder's concept of freedom and sovereignty. She was a convert to Catholicism and was persecuted by the Nazis.

Carl Schmitt: A legal theorist whose concept of sovereignty, based on the ability to make exceptions to rules, is presented as a "puerile, a boyish joke" by Snyder, contrasting with his own definition of sovereignty rooted in individual self-knowledge and values.

Liviy: A Roman historian who defined freedom as "standing upright oneself without depending on another’s will." Snyder critiques this definition as insufficient for understanding the needs of the very young.

Václav Havel: A Czech dissident, playwright, and later president of Czechoslovakia. His ideas about "living in truth," normality, unpredictability, and the "power of the powerless" are significant inspirations for Snyder's work on freedom and dissidence.

Jan Patočka: A Czech philosopher and moral authority mentioned as an influence on Václav Havel.

Leszek Kołakowski: A Polish philosopher forced into exile after the events of 1968. He is described as a moral authority for Adam Michnik and a friend of Snyder's. His ideas about the plurality and antagonism of virtues in the "world of values" are discussed.

Adam Michnik: A Polish dissident and friend of Snyder's, known for his work arising during periods of incarceration. He is mentioned as a visitor at Yale.

Dwayne: One of Timothy Snyder's incarcerated students who was captivated by Edith Stein's work and provided insightful summaries of her arguments on the body and empathy.

Alpha: One of Timothy Snyder's students who gave him a "white-guy hug" as a joke after reading a revised version of the text.

Vladimir Putin: The current leader of Russia, presented as a figure who denies the existence of the Ukrainian nation and promotes a politics of eternity and inevitability, in opposition to freedom and the future. His imperialist views on Ukraine are discussed.

Adolf Hitler: The leader of Nazi Germany, whose worldview denying the "world of values" and viewing Jews as "foreign bodies" is sharply contrasted with Edith Stein's philosophy and Snyder's concept of freedom. His plans for Eastern Europe, particularly Ukraine, as "living space" are mentioned.

Joseph Stalin: The leader of the Soviet Union, associated with a totalitarian regime and a politics that allowed for a single, defined future (the fourth dimension) and a single value (communism, the fifth dimension), thereby limiting freedom.

Boris Yeltsin: Leader of communists in Russia who spoke for a greater role for the Russian republic during the disintegration of the USSR. He later became the first President of Russia.

Michael Stipe: The lead singer of R.E.M., who was inspired by the Velvet Underground.

Velvet Underground: A rock band that influenced R.E.M. and is linked to the Plastic People of the Universe through Václav Havel's appreciation of their music.

Plastic People of the Universe: A Czech rock band whose persecution by the communist regime was a catalyst for the human rights movement Charter 77, supported by Václav Havel.

Wilhelm von Habsburg (Vasyl Vyshyvanyi): An unpredictable figure whose life ended in Soviet prison. His chosen Ukrainian name is noted, as is the later significance of Ukraine.

Mustafa Nayyem: A Ukrainian figure mentioned in the context of the Maidan protests.

Serhiy Zhadan: A Ukrainian writer and artist mentioned in the context of the Maidan protests and infrastructure.

Volodymyr Zelens’kyi: The President of Ukraine, mentioned in the context of the second Russian invasion and the importance of truth.

Victoria Amelina: A Ukrainian writer and figure whose work is discussed in relation to testifying to truth in times of war.

Volodymyr Vakulenko: A Ukrainian writer whose work is discussed in relation to testifying to truth in times of war.

Austin Reed: Mentioned in relation to his memoir written in prison, The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict.

Julius Margolin: Mentioned for his memoir of the Gulag.

Lord Acton: Quoted on the monstrous nature of error that has no one to believe it.

James Baldwin: Quoted on the "freedom which cannot be legislated."

Leszek Kołakowski: Quoted on the "horizon of truth."

Haruki Murakami: A Japanese novelist mentioned for writing about "relationship from wound to wound."

Jerome Groopman: Mentioned in relation to how doctors think.

Ivan Ilyin: A Russian fascist philosopher whose ideas are mentioned in the notes as being cited by Vladislav Surkov.

Vladislav Surkov: A Russian thinker who is noted for maintaining that the sovereignty of the state means the sovereignty of one person, the dictator, citing Ilyin.

Thomas Bernhard: An Austrian writer whose play Heldenplatz is noted as a classic artistic rendering of the mood in Vienna when Hitler arrived.

Martin Pollack: Noted for a summary of the pogrom mood in Vienna.

Gerhard Botz: Noted for a book on National Socialism in Vienna.

Simone Weil: A philosopher whose ideas are referenced on attention span, capitalism, confirmation bias, free speech, habitus, loneliness, paying forward, solidarity, sovereignty, unpredictability, and the world of values.

Isaiah Berlin: Mentioned for his famous treatment of positive and negative freedom, which Snyder engages with and critiques.

Charles Taylor: Mentioned as having shown how positive and negative freedom collapse together philosophically.

Dan Stone: Mentioned for his book on the liberation of the camps, which inspired Snyder's thinking.

Rutger Bregman: Mentioned for his book Humankind, referencing the need for children to have places to play.

Der Nister: A Jewish novelist whose novel is compared to Dostoevsky's study of character. He died in a prison hospital during Stalin's anti-Semitic purge.

Vasily Grossman: A novelist whose works are mentioned as having shaped Snyder's historical work and influenced his argument on empathy.

Immanuel Kant: Mentioned in relation to free will and practical reason.

Susanne Batzdorff: Mentioned for a book on Edith Stein.

Pius XI: A Pope to whom Edith Stein wrote a letter.

Roman Ingarden: A philosopher to whom Edith Stein wrote a letter.

Thomas Hobbes: Mentioned as part of a tradition of social contract theory.

John Locke: Mentioned as part of a tradition of social contract theory.

Plato: Mentioned in relation to state sovereignty, the problem of new things arising, and his works Laws and Republic.

Jean Bodin: Mentioned as having a powerful description of state sovereignty.

Ernst Bloch: Mentioned for his remark on inequality in his first book.

Rüdiger Safranski: Mentioned for his remark on a person being defined by not permitting themselves to be defined.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Mentioned for a moment in his novel Vol de nuit that illustrates a single virtue having an absolute claim.

James Madison: Quoted on the necessity of virtue for liberty.

Hannah Arendt: Mentioned as holding the view that the highest human achievement was the creation of virtues.

Friedrich Nietzsche: Mentioned as holding the view that the highest human achievement was the creation of virtues.

Thomas Bernhard: Mentioned for hearing a remark from his grandfather about "mosaic stones."

B.F. Skinner: Mentioned in relation to the discovery of shaping in behaviorism.

Roger McNamee: Mentioned for his book on brain hacks and social media.

Ayn Rand: Mentioned as a "Bolshevik à rebours."

Herman Melville: Mentioned for his remark in "Bartleby the Scrivener" on the wearing out of good resolves by illiberal minds.

Lee McIntyre: Mentioned for his book on post-truth and brain hacks.

Peter Longerich: Mentioned for his books on Nazi Germany.

Thomas Kühne: Mentioned for his book on belonging and genocide.

David M. Glantz: Mentioned as the editor of Hitler and His Generals.

Gerhard L. Weinberg: Mentioned as the editor of Hitler's Second Book.

Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens: Mentioned as translators of Hitler's Table Talk.

Eberhard Jäckel and Axel Kuhn: Mentioned as editors of Hitler's early writings.

Andreas Hillgruber: Mentioned as the editor of records of Hitler's conversations with foreign representatives.

Johann Chapoutot: Mentioned for an article on Nazi historicity.

Reinhart Koselleck: Mentioned for his work on the fourth dimension (the future).

Christian Gerlach: Mentioned for appreciating the role of food in Hitler's practice.

Heimito von Doderer: Mentioned for a remark in his novel about "progress reeking of oil."

Edouard I. Kolchinsky et al.: Mentioned for an article on "Russia's New Lysenkoism."

Krzysztof Michalski: Mentioned for quoting Leszek Kołakowski on the "horizon of truth."

Marcin Król: Mentioned for a book.

Frank Golczewski: Mentioned for a book on Germans and Ukrainians.

Peter Borowsky: Mentioned for a book on German Ukraine policy in 1918.

Gerald Feldman: Mentioned for a book on German Imperialism.

L. Gelber and Romaeus Leuven: Mentioned as editors of Edith Stein's Life in a Jewish Family.

Lynne Viola: Mentioned for an article on the self-colonization of the Soviet Union.

Alexander Etkind: Mentioned for his book Internal Colonization.

Karel C. Berkhoff: Mentioned for his book Harvest of Despair.

Wendy Lower: Mentioned for her book Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine.

Jerzy Giedroyc: Mentioned for his autobiography, which deals with the Polish colonial tradition.

Czesław Madajczyk: Mentioned for an article on legal conceptions in the Third Reich.

Mark Edele and Michael Geyer: Mentioned for their chapter on states of exception.

Stephen G. Wheatcroft: Mentioned for an article on agency and terror in Stalin's Great Terror.

Yedida Kanfer: Responsible for transcribing conversations for Snyder's collaborative work with Tony Judt.

Tony Judt: Co-authored Thinking the Twentieth Century with Timothy Snyder.

Marci Shore: Mentioned for her forthcoming history of phenomenology in central and eastern Europe.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Mentioned for a passage illustrating a single virtue having an absolute claim.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Mentioned for a passage illustrating a single virtue having an absolute claim.

Gail B. Peterson: Mentioned for an article on B.F. Skinner's discovery of shaping.

Tomas Venclova: Mentioned in the context of factuality.

Richard Rorty: Mentioned in the context of the middle class.

Arundhati Roy: Mentioned in the context of the wolf's word.

Zhenya Monastyrs’kyi: Mentioned in the context of confinement.

Y.F. Mebrahtu: Mentioned in the context of freedom and infrastructure.

Hugo Portisch: Mentioned in the context of news and freedom of speech.

Danny Gubits: Mentioned in the context of the rings of time.

George Schwab: Mentioned as translator of Carl Schmitt's The Concept of the Political.

Jean-Pierre Faye: Mentioned for an article on Carl Schmitt.

Yves Charles Zarka: Mentioned as editor of a volume on Carl Schmitt and author of a book on a Nazi detail in Schmitt's thought.

Herlinde Pauer-Studer and Julian Find: Mentioned as editors of a volume on justifications of injustice.

Joel Golb: Mentioned as translator of Raphael Gross's book on Carl Schmitt and the Jews.

Sheila Fitzpatrick: Mentioned as editor of a volume on totalitarianism.

Tony Judt with Timothy Snyder: Co-authors of Thinking the Twentieth Century.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Mentioned again, this time for a passage in Vol de nuit.

FAQ

What is the central idea of freedom according to the author?

The author posits that freedom is not merely an absence of constraints (often referred to as "negative freedom") but is a "positive presence." It's an active state of being where individuals can make choices based on their values and bring those choices into the world. This requires the "de-occupation of our minds from the wrong ideas" and the recognition that freedom is the fundamental condition that allows for the flourishing of "all the good things." It's the "absolute among absolutes, the value of values," not because it's the only good, but because it enables the existence and realization of all other virtues and good things.

How does the concept of "Leib" versus "Körper" relate to understanding freedom?

Drawing on the work of Edith Stein, the author introduces the German terms "Körper" and "Leib" to distinguish between different understandings of the body. "Körper" refers to the body as a physical object, subject to physical laws, like a "foreign body" or a "heavenly body." It can exist without "me." In contrast, "Leib" designates a living human body, with its own internal rules, capacity for feeling, movement, and a unique "zero point" or center. The author argues that true freedom begins with understanding ourselves as "Leib," not just "Körper." Moreover, recognizing others as "Leib" and engaging in empathy allows us to gain objective knowledge about ourselves and the world, liberating us from seeing ourselves as isolated individuals. This shared liveliness and mutual recognition are crucial for developing the self-knowledge needed for sovereignty and freedom.

What does the author mean by "sovereignty" and how is it achieved?

Sovereignty, in this context, refers to personal autonomy – the ability of an individual to know themselves and the world sufficiently to make judgments about values and act upon them. It's not about absolute independence but about exercising one's will and realizing combinations of commitments in the world. The author illustrates this through the act of pitching a baseball, where visualizing a desired outcome and executing the pitch is a humble form of sovereignty. Sovereignty is achieved through the practice of making choices based on values, navigating the space between the "law of necessity" (the physical world) and the "law of freedom" (the world of values). It's a continuous process of working, learning, and inventing ourselves through our choices, which in turn makes the world more unpredictable and us more responsible. It requires support from others, especially during formative years, and is not a state of being that is simply "given."

How do historical examples, like those involving the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, illuminate the author's ideas about freedom and unfreedom?

The historical examples provide stark contrasts to the author's vision of freedom. The disintegration of the Soviet Union, for instance, is linked to the failure of a system based on a single, predetermined future and value (communism), highlighting the importance of plurality and unpredictability for freedom. Nazi Germany, under Hitler, represents an extreme form of unfreedom by denying the existence of a "world of values" and reducing human existence to a three-dimensional struggle for survival based on racial ideology. Hitler's concept of "Lebensraum" (living space) in Ukraine, for example, is presented as a murderous colonial fantasy that stripped both Germans and their victims of their fourth (future) and fifth (values) dimensions of existence. These examples underscore that attempts to impose a single, predetermined reality or deny the inherent dignity and value of individuals lead to profound unfreedom.

What is the "world of values" and how does it interact with the physical world?

The "world of values" is described as a "fifth dimension," distinct from the four dimensions of space and time that constitute the physical world. It is the realm of "good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice." This dimension has its own rules, which are distinct from physical laws. The author emphasizes that virtues are real and have an absolute claim on us, but they often conflict with one another (e.g., honesty and loyalty). Freedom involves navigating these conflicting claims and making choices that bring values into the physical world through our actions. While we don't create the world of values or the physical world, we can create "small passages between them," making our actions meaningful and contributing to the unpredictability of the world.

How does the concept of unpredictability relate to freedom?

Unpredictability is presented as a key characteristic of free individuals and societies. It arises from the unique combination of circumstances, choices, and values that each sovereign person embodies. When individuals are sovereign, their choices are not predetermined but are made in the dynamic space between the physical world and the world of values. This process of choosing and acting injects unpredictability into the four-dimensional world. When people are "sovereign together," this unpredictability is amplified and mutually recognized, leading to a richer and more dynamic social environment. Systems that aim to make people predictable, such as authoritarian states or manipulative digital technologies, are fundamentally opposed to freedom.

What role does community and solidarity play in the development and maintenance of freedom?

Although freedom is ultimately a quality of the individual life (the "Leib"), it is profoundly dependent on community and solidarity. The author emphasizes that we are born dependent and require the goodwill of others to develop into sovereign individuals. Language, education, and a shared past are all transmitted through community. Furthermore, recognizing others as "Leib" and practicing empathy is essential for objective self-knowledge and understanding the world. Solidarity, demonstrated in actions like the Good Samaritan's compassion or the collective efforts of Ukrainian citizens, involves recognizing the shared human predicament and acting to alleviate the unfreedom of others. Freedom is not a solitary pursuit; it is "the work of generations" and requires continuous examination and support within a community.

Why does the author argue that democracy is the best political system for freedom?

The author argues that democracy is the political system towards which the different forms of freedom lead, serving as "the best resolution of freedom as a principle." This is because genuine democracy relies on the sovereignty of "We the people," which in turn depends on the sovereignty of individual persons. The unpredictable voter in a fair election commands the attention of candidates, and a socially mobile person, who believes in a better future, is more likely to engage in the democratic process. Solidarity, another key element of freedom, manifests in caring about the votes and well-being of others, which is crucial for a functioning democracy. Therefore, the development of individual sovereignty, unpredictability, mobility, and solidarity among citizens naturally points towards a democratic system that can accommodate and facilitate these aspects of freedom.

Table of Contents with Timestamps

00:00 - Introduction

Introduction to Heliox podcast and its approach to deep yet accessible conversations.

00:40 - Framing the Discussion on Freedom

Introduction to Timothy Snyder's book "On Freedom" and the podcast's mission to unpack deeper meanings of freedom.

01:18 - Negative Freedom vs. Positive Freedom

Exploring the concept of "freedom from" (negative freedom) and its limitations.

01:38 - The Ukrainian Perspective

How Ukrainians facing invasion demonstrated a more active "freedom for" rather than just "freedom from."

02:55 - The Individual Nature of Freedom

Snyder's argument that only individuals can be free, not abstract entities like the state or market.

03:16 - Historical Complications of Freedom

Discussion of how definitions of freedom have historically served the powerful, including examples of slave owners.

03:55 - Snyder's Personal Context

Exploration of Timothy Snyder's background and experiences that shaped his understanding of freedom.

05:38 - Soviet Collapse and Western Misinterpretation

Analysis of how the West's simplified view of the Soviet collapse as a "victory for capitalism" missed crucial complexities.

06:49 - Rise of Russian Oligarchy

Discussion of how the transition from Soviet system led to oligarchy rather than genuine freedom.

07:24 - The Vulnerability of Negative Freedom

How societies focused solely on negative freedom become vulnerable to power grabs and propaganda.

08:39 - Positive Freedom as Alternative

Introduction to Snyder's proposed alternative: positive freedom as active engagement.

09:15 - Leib and Körper

Explanation of German philosophical terms distinguishing the body as object (Körper) from the body as lived experience (Leib).

11:22 - Cultivating Positive Freedom

How to develop positive freedom through empathy and understanding others as subjects.

12:16 - Freedom Through Practice

Discussion of how practiced activities create a form of liberation through skilled, unselfconscious movement.

12:39 - The World of Values

Exploration of Edith Stein's concept of values existing beyond the physical world.

13:24 - Conclusion

Synthesis of the discussion: true freedom is active, engaged, and involves recognizing humanity in ourselves and others.

14:33 - Podcast Closing

Closing remarks about Heliox's four recurring narrative frameworks.

Index with Timestamps

Agency, 02:29

American exceptionalism, 08:08

Appendix (Snyder's personal story), 11:40

Art, 10:52

Bells (exiled in Russia), 05:24

Capitalism, 05:50, 06:15, 06:45, 08:08

Cold War, 06:05

Collective voice, 05:24, 09:04

Edith Stein, 11:22, 12:39

Efficiency (government), 04:55

Empathy, 09:45, 11:22, 13:36, 14:05

Freedom from (negative freedom), 01:03, 01:18, 06:00, 08:39, 09:54, 13:24

Freedom for (positive freedom), 01:49, 08:39, 10:03, 13:24

German philosophical terms, 09:15

Habitude and grace, 12:11

Holocaust, 04:46

Invasion (Ukraine), 01:37, 07:10

Körper (body as object), 09:15, 11:45

Leib (body as subject), 09:15, 11:45, 11:58, 13:34

Liberty bell, 03:40

Martial law (Poland), 04:23

Monopolies, 06:45, 08:08

Moscow (Snyder's experience in), 05:05

Negative freedom, 01:03, 01:18, 06:00, 08:39, 09:54, 13:24

Ohio (Snyder's roots), 03:57

Oligarchy, 05:54, 06:59, 08:36

Pain, 10:38, 10:47

Polarization (U.S.), 08:19

Positive freedom, 08:39, 10:03, 11:22, 13:24

Practice (freedom through), 12:16

Propaganda, 07:12, 08:17

Putin, 06:45, 07:00

Russian social media campaigns, 08:19

Self-deception, 10:03

Simone Weil, 11:27

Slave owners, 03:27

Social media campaigns (Russian), 08:19

Soviet economy, 05:05

Soviet Union collapse, 06:09

Subjectivity (shared), 10:10, 11:39

Timothy Snyder, 00:45

Ukraine, 01:38, 07:10, 08:28, 08:46

Values (world of), 12:39, 13:03

Vulnerability, 07:24, 12:04

World of values, 12:39, 13:03

Yeltsin dissolving parliament, 06:32

Poll

Post-Episode Fact Check

Negative vs. Positive Freedom

Claim: The podcast distinguishes between "negative freedom" (freedom from constraints) and "positive freedom" (freedom for something)

Fact Check: ACCURATE - This distinction is well-established in political philosophy, dating back to Isaiah Berlin's 1958 essay "Two Concepts of Liberty," where he distinguishes between negative liberty (absence of constraints) and positive liberty (presence of control or self-determination).

Ukrainian Resistance Framing

Claim: Ukrainians fighting Russian invasion framed their struggle in terms of "freedom for" rather than just "freedom from"

Fact Check: PARTIALLY VERIFIED - While many Ukrainian statements about resistance did emphasize future aspirations beyond just removing Russian forces, a comprehensive study of how Ukrainians framed their resistance would require specific sources not cited in the podcast.

Leib and Körper Concepts

Claim: The podcast uses German philosophical terms "Leib" (body as subject) and "Körper" (body as object)

Fact Check: ACCURATE - These are legitimate phenomenological concepts in German philosophy, particularly developed by Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, distinguishing between the lived experience of embodiment and the body as physical object.

Soviet Union Collapse Interpretation

Claim: The collapse of the Soviet Union was widely interpreted in the U.S. as a simple victory for capitalism and negative freedom

Fact Check: BROADLY ACCURATE - Francis Fukuyama's influential 1992 book "The End of History and the Last Man" exemplifies this view, arguing that Western liberal democracy represented the final form of human government. This perspective was indeed widespread in American political discourse.

Yeltsin Dissolving Parliament

Claim: Boris Yeltsin dissolved the Russian parliament by force in 1993

Fact Check: ACCURATE - In September-October 1993, Yeltsin issued decree 1400 dissolving the parliament, leading to the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis and armed conflict in Moscow with Yeltsin using military force against the parliament building.

Russian Oligarchy Development

Claim: The transition from Soviet system led to oligarchy rather than genuine democracy

Fact Check: ACCURATE - Russia's post-Soviet privatization program, particularly the "loans-for-shares" scheme of 1995-1996, transferred vast state assets to a small group of businessmen who became known as oligarchs, consolidating economic power among a select few.

Putin's Rise Following Oligarchy

Claim: Putin consolidated power on top of the oligarchic structure

Fact Check: ACCURATE - Vladimir Putin came to power in 1999-2000 and established what political scientists call a system of "managed democracy," where he balanced relationships with oligarchs while bringing them under state control and replacing some with allies.

Russian Election Interference

Claim: Russia attempted to rig Ukrainian elections in 2004

Fact Check: ACCURATE - The 2004 Ukrainian presidential election was marked by widespread fraud favoring pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych, leading to the Orange Revolution. Independent electoral observers and subsequent Ukrainian Supreme Court decisions confirmed election tampering.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine 2014

Claim: Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014

Fact Check: ACCURATE - In February-March 2014, following the Ukrainian Revolution, Russia annexed Crimea and supported separatist movements in eastern Ukraine's Donbas region, constituting what international organizations and most countries recognized as an invasion.

Russian Social Media Campaigns

Claim: Russia conducted social media campaigns targeting U.S. politics around 2016

Fact Check: ACCURATE - The U.S. intelligence community, Mueller investigation, and Senate Intelligence Committee all concluded that Russia conducted systematic social media influence operations targeting the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Philosophers Mentioned

Claim: The podcast references Edith Stein and Simone Weil as philosophers who wrote about empathy and seeing others

Fact Check: ACCURATE - Edith Stein wrote "On the Problem of Empathy" (1916) and Simone Weil's works, including "Gravity and Grace," extensively discuss the ethical importance of attention to others.

Wealth Concentration in the U.S.

Claim: The U.S. has experienced increasing wealth concentration and monopolistic tendencies

Fact Check: ACCURATE - Economic data confirms increasing wealth inequality in the U.S. since the 1970s. The top 1% of U.S. households held 32.3% of the nation's wealth as of 2021, up from 23.6% in 1989. Market concentration has also increased in many sectors.

Timothy Snyder's Background

Claim: Snyder had academic experiences in Moscow around 1990 studying the Soviet economy

Fact Check: PLAUSIBLE - Snyder is a historian specializing in Eastern European history. While his specific time in Moscow in 1990 isn't independently verified in this fact check, he has written extensively about Soviet and post-Soviet history, suggesting relevant research experience.

Values World Concept

Claim: Edith Stein developed the concept of a "world of values" beyond physical reality

Fact Check: ACCURATE - Stein's phenomenological work, influenced by Edmund Husserl and Max Scheler, includes the concept of value-essences and a realm of values that exists beyond physical reality but can be accessed through intentional acts.

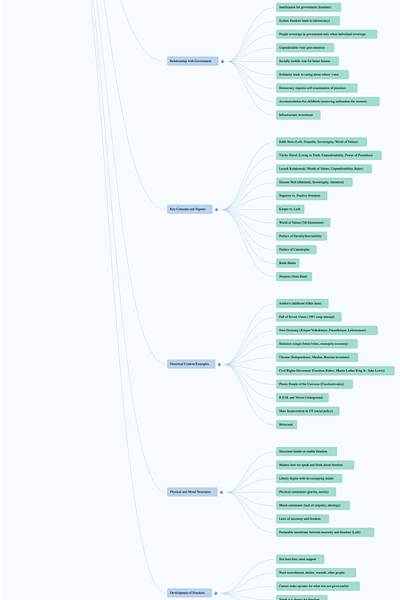

Image (3000 x 3000 pixels)

Mind Map