The Conscience Crisis: Understanding Moral Injury

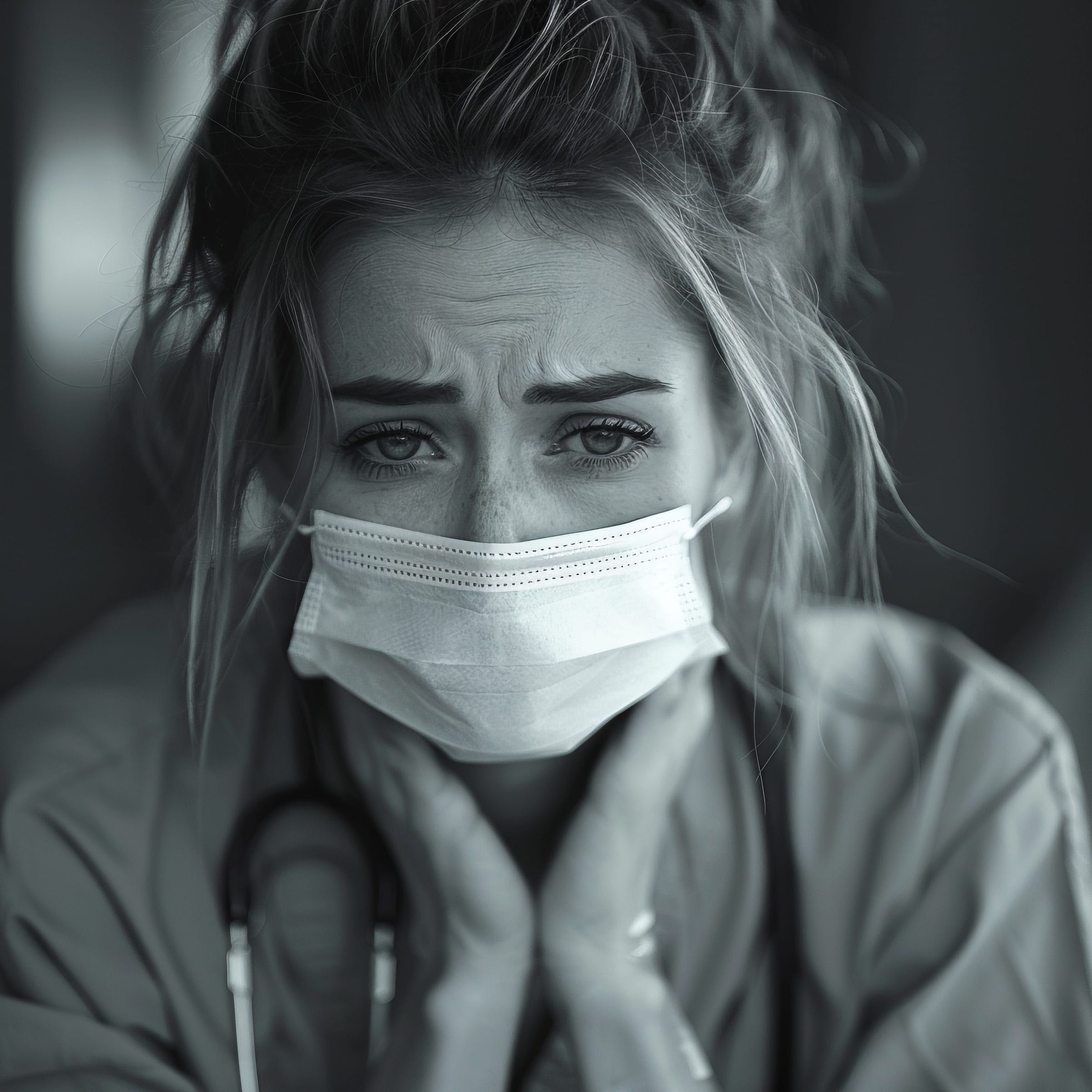

Moral injury leads to burnout and abandoning careers, it manifests as harsh self-criticism and alarmingly high rates of suicidal ideation.

With every article and podcast episode, we provide comprehensive study materials: References, Executive Summary, Briefing Document, Quiz, Essay Questions, Glossary, Timeline, Cast, FAQ, Table of Contents, Index, 3k Image, and Fact Check.

Please support my work by becoming a free subscriber. (Your subscription helps me continue providing evidence-based analysis in a media landscape increasingly hostile to inconvenient truths.)

We live in a society that loves heroes until they break.

We applaud the firefighter running into burning buildings, celebrate the paramedic saving lives, and thank veterans for their service. But when these same people come home carrying invisible wounds that cut deeper than any physical injury, we suddenly don't know what to do with them.

There's a type of trauma we barely talk about, one that doesn't fit neatly into our existing mental health frameworks. It's called moral injury, and it's quietly destroying the people we depend on most.

The Wound That Medicine Forgot

For decades, we've understood trauma through the lens of PTSD—fear-based reactions to terrifying events. But what happens when the deepest wound isn't from what you witnessed, but from what you were forced to do? Or couldn't prevent? What happens when the injury isn't to your sense of safety, but to your sense of self?

That's moral injury. It's what happens when someone violates their own deeply held values, witnesses others do so, or gets betrayed by institutions they trusted. It's not "I'm afraid this will happen again"—it's "I can't live with what I've done" or "I can't believe I let this happen."

The difference is crucial. PTSD says "I did something bad." Moral injury whispers "I am bad because of what I did."

The Perfect Storm for Our Essential Workers

Think about the impossible situations we regularly place our essential workers in. The paramedic who has to choose which patient gets the last ventilator. The police officer who watches a colleague use excessive force and feels powerless to intervene. The healthcare worker who follows organizational policies that they know will harm patients.

During COVID-19, we saw this play out in real time. Healthcare workers weren't just dealing with the fear of infection—they were grappling with having to ration care, potentially infecting their own families, and working within systems that prioritized profit over patient care. Many left the profession entirely, not because they were afraid, but because they couldn't reconcile their actions with their values.

We called them heroes while putting them in situations that made them feel like villains.

The Ripple Effects We're Not Talking About

Moral injury doesn't stay contained. It metastasizes through every aspect of a person's life. Professionally, it leads to burnout and people abandoning careers they once loved. Psychologically, it manifests as harsh self-criticism and alarmingly high rates of suicidal ideation—rates that remain elevated even when accounting for other mental health conditions.

But perhaps most devastatingly, it attacks spirituality and meaning-making. People with moral injury often lose faith in humanity, in justice, in the very concepts that once motivated them to serve others. They withdraw from relationships, unable to connect with people who haven't experienced what they have.

The cruel irony? The very qualities that make someone excellent at helping others—strong moral convictions, a sense of duty, empathy—are the same qualities that make them vulnerable to moral injury.

The Systems That Fail Them

Here's what makes me angry: moral injury isn't always about individual failures. Often, it's about systemic ones. Organizations that prioritize metrics over people. Leaders who make decisions from boardrooms while others implement them on the ground. Policies written by people who will never have to follow them.

When a paramedic feels guilty for not saving someone because their equipment was faulty—equipment the department knew was faulty but didn't replace due to budget constraints—that's not individual failure. That's institutional betrayal.

When a police officer witnesses corruption and stays silent because they know speaking up will end their career and their family's livelihood, that's not moral weakness. That's a system that punishes integrity.

The Gender and Equity Dimension

The research reveals something particularly troubling: moral injury doesn't affect everyone equally. Women in public safety roles experience higher rates of betrayal-based moral injury, often from their own organizations. People from marginalized communities face additional layers of moral burden, especially when they're forced to participate in or witness systems that perpetuate the discrimination they themselves have experienced.

A Black police officer enforcing policies they believe are racially biased. A female firefighter enduring sexual harassment while trying to save lives. These aren't just individual struggles—they're symptoms of deeper systemic problems that we're failing to address.

The Path Forward

But here's what gives me hope: unlike some forms of trauma, moral injury can actually lead to growth. When people successfully work through moral injury, they often emerge with stronger, clearer values and a renewed sense of purpose. They develop what researchers call "moral resilience"—the ability to maintain their integrity even in impossible situations.

The key is creating environments where people can process these experiences without judgment. This means organizational leaders need to acknowledge the moral dimensions of the work they're asking people to do. It means providing support that goes beyond traditional trauma therapy to address the spiritual and ethical wounds.

It means recognizing that some of our heroes are breaking not because they're weak, but because they care too much.

What We Owe Them

We have a moral obligation to the people who serve our communities. Not just to thank them for their service, but to create conditions where they can serve without sacrificing their souls. This means better training, clearer ethical guidelines, psychological safety in the workplace, and leaders who understand the weight of the decisions they're making.

Most importantly, it means acknowledging that moral injury is real, it's treatable, and it's often preventable.

We created the conditions that wound our heroes. We have the power to create conditions that heal them.

References:

The Difference Between Moral Injury and PTSD

PTSD: National Center for PTSD

Find us:

YouTube

Substack

Podcast Providers

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Patreon

FaceBook Group

STUDY MATERIALS

1. Briefing Document

1. Introduction to Moral Injury (MI)

Moral Injury (MI) is a distinct psychological phenomenon that arises when an individual experiences or witnesses events that profoundly contradict their deeply held moral beliefs, values, or ethical expectations. While often associated with military personnel and veterans, MI can affect anyone in high-stakes, morally challenging professions, such as public safety personnel (PSP), including firefighters, paramedics, and police officers. It is crucial to understand that MI is not merely a mental disorder but rather a "dimensional problem" involving psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual harm.

2. Differentiating Moral Injury from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

While MI and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) share some overlapping symptoms and often co-occur, they are recognized as distinct conditions with different underlying mechanisms.

Key Distinctions:

Mechanism of Injury:PTSD: Results from "exposure to a substantial threat of physical harm to one’s self or others (i.e., PPTE)." This involves "actual or threatened death, injury, or other threat to physical integrity."

Moral Injury: Stems from "exposure to a transgression of morals, ethics, or values (i.e., PMIE)." The individual must feel "a transgression occurred and that they or someone else crossed a line with respect to their moral beliefs."

Nature of the Condition:PTSD: Recognized by the VA as a "mental disorder that requires a diagnosis."

Moral Injury: Considered a "dimensional problem" rather than a formal mental disorder within diagnostic systems like DSM-5-TR or ICD-10. However, "there may be a Moral Injury Disorder in the future."

Core Emotional Responses:While both can involve guilt and shame, these are "core features of moral injury" and "PTSD diagnosis doesn’t adequately or accurately represent the shame and guilt of moral injury."

MI often involves profound feelings of "grief, guilt, and shame," "disgust," and "anger" specifically tied to the moral transgression.

Betrayal: "Betrayal from leadership, others in positions of power or peers" is a significant component of MI, leading to "loss of trust." While betrayal can be a feature of PTSD (e.g., assault by a loved one), it is central to MI.

Symptom Profile: PTSD includes additional symptoms like "hyperarousal that are not central to moral injury." Studies suggest that "perpetration-based events (events where someone perpetrated an act outside of one's values) were associated with more re-experiencing, guilt, and self-blame than were life threatening traumatic events."

Co-occurrence and Severity: "Having moral injury in addition to PTSD is associated with greater PTSD and depression symptom severity and greater likelihood of suicidal intent and behaviors."

3. Defining Morals, Ethics, and Values in the Context of MI

The concept of moral injury is deeply rooted in an individual's personal framework of morals, ethics, and values.

Morals: These are "universal laws that set the foundation for how societies, organizations, professions, and individuals behave regardless of personal characteristics." They are fundamental principles of right and wrong.

Ethics: "Ethics are specific, context-driven codes of behaviour that are based upon morals." They are "the expression of moral rules" within a particular context, such as a professional code for paramedics or police.

Values: These are "concepts based on morals and ethics that a person can freely choose, and which guide a person’s beliefs and actions." Unlike morals and ethics which are external ("how I ought or am supposed to live"), values are internal and reflect "who a person is as an individual." "Core values" are "the fundamental values for a person’s sense of self."

4. How Moral Injury Occurs: Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs)

MI results from exposure to Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs), which are actions, inactions, or events that violate an individual's deeply held moral, ethical, or core values.

Types of PMIEs:

Acts of Commission: "purposeful behaviors undertaken by a person (i.e., something that was done)." For soldiers, this could include "participation in killing others."

Acts of Omission: "when they fail to do something in line with their beliefs." For soldiers, this might be "not preventing other soldiers from performing immoral acts."

Betrayal: "MEV transgression committed by a trusted person or group of people." This can involve "betrayal from leadership, others in positions of power or peers." Examples include being "endangered because their organization did not provide sufficient resources for an assigned duty."

These transgressions "shatter moral and ethical expectations that are rooted in ethical or spiritual beliefs, or culture-based, organizational, and group-based rules about fairness and the value of life."

5. Symptoms and Impacts of Moral Injury

Moral injury manifests in a wide range of symptoms, impacting various domains of life and well-being. Some symptoms overlap with PTSD, while others are more specific to MI.

Overlapping Symptoms with PTSD:

Anger

Depression

Insomnia

Nightmares

Anxiety

Substance abuse

Symptoms Specific to Moral Injury:

Grief, Guilt, and Shame: "ongoing, continuous feelings of negativity," regret about "acts or behaviors you participated in or witnessed without speaking up." Shame "is when the belief about the event generalizes to the whole self (e.g., 'I am bad because of what I did.')"

Social Alienation/Withdrawal: "a veteran may withdraw and become isolated, rejecting loved ones, friends, and other people in his environment." This can involve "feeling disconnected from important other people" and "actively avoiding intimate relationships."

Lack of Trust and Difficulty with Forgiveness: Inability to "self-forgive" can lead to a breakdown in trust in "themselves, friends, family, and the world they live in." This can result in "self-sabotaging behaviors (e.g., feeling like you don't deserve to succeed at work or relationships)."

Anhedonia: The "inability to feel pleasure," affecting both social (not wanting to spend time with others) and physical (not finding pleasure in sensations like hugs or sex) domains.

Damage to Character and Identity: MI "has been described as damage suffered to one’s character, identity, and deepest sense of self." Individuals may feel "they 'have lost themself,' 'are broken,' 'are not who they used to be,' or 'do not know who they are any more'."

Spiritual/Existential Struggles: "loss of faith or previous spiritual or religious beliefs," "confusion or dissonance surrounding one’s spiritual or religious beliefs," "perceived alienation from a Higher Power," "fractured world-beliefs," and "loss of meaning and purpose."

Occupational Difficulties: "decreased work engagement and challenges like burnout, compassion fatigue, numbing/cynicism, or absenteeism."

6. Assessment and Treatment of Moral Injury

Assessing and treating moral injury requires specific approaches that acknowledge its unique characteristics.

Assessment:

It is vital to "identify exposure to a potentially morally injurious event (PMIE) and assess moral injury symptoms directly linked to this PMIE."

Specific psychometric tools have been developed, such as the Moral Injury Outcomes Scale (MIOS) and the Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS).

Other measures like the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory and Trauma Related Shame Inventory can assess core features.

Treatment Approaches:

Therapeutic Stance: Therapists must convey "an accepting, non-judgmental, empathic stance," as patients may feel intense "guilt and shame" and fear judgment. Addressing beliefs that they "do not deserve to feel better" is crucial for engagement.

Integration with PTSD Treatments: Some trauma-focused PTSD treatments like Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) can reduce trauma-related guilt and shame, though some studies suggest these symptoms might endure and require further, specialized treatment. It's important that "the traumatic event(s) processed in therapy were not the ones that involved trauma-related guilt" or that patients are willing to share their "worst traumatic event."

MI-Specific Treatments (under investigation):Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) adapted for MI: Focuses on "helping patients live in accordance with values."

Adaptive Disclosure: Uses "imaginary dialogue with a compassionate moral authority" to process MI, apportion blame, and make amends, often incorporating self-compassion and mindfulness.

The Impact of Killing intervention: A phased individual therapy that explores the functional impact of self-unforgiveness, develops forgiveness plans (e.g., letter writing to those killed), and amends plans.

The Moral Injury Group: A group intervention co-delivered by a chaplain and psychologist, including "a ceremony where participants share testimonies of their moral injury with the public."

Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (TrIGR): Helps patients identify and evaluate beliefs contributing to guilt and shame, identify violated values, and make plans to live in line with those values.

Building Spiritual Strength: An 8-session group therapy led by a chaplain, addressing "concerns about relationship with a Higher Power as well as challenges with forgiveness."

Role of Spirituality and Chaplains: "Existential, spiritual, or religious struggles can be core features of an MI." Religious or spiritual guidance from chaplains can be helpful for managing moral symptoms, promoting "evidence-based spiritual coping strategies (i.e., mediation, prayer, self-compassion, forgiveness)."

Meaning-Making: "Making meaning out of a PMIE has been associated with the mitigation of negative impacts from an MI." This involves acknowledging the PMIE, identifying symptoms, restoring or revising morals/ethics/values, and integrating actions into a larger narrative. Expressive writing and spiritual practices can aid this process.

7. Broader Context and Future Directions

While initially studied in military veterans, "moral injury can occur outside of the military context," affecting other PSP and potentially broader populations.

The widespread attention to MI indicates its resonance with individuals who have experienced such events and with clinicians and researchers.

A "biopsychosociospiritual model" is recommended for understanding and addressing MI in treatment.

The concept of Moral Resilience describes the "ability to adapt, resolve, and overcome the adversity associated with a PMIE exposure, ultimately regaining a sense of identity, purpose, and wholeness." This involves addressing personal limitations, identifying one's moral compass, and constructively addressing systemic or personal factors that led to the PMIE.

Moral Strength is "a person’s capacity, motivation, and willingness to take moral action."

Increased self-awareness, psychoeducation about PMIEs and MI, learning to recognize symptoms, distinguishing "who one is" from "what one has done or has not done," and engaging in self-reflection are crucial steps for individuals and teams in high-risk professions.

2. Quiz & Answer Key

Quiz:

Instructions: Answer each question in 2-3 sentences.

How does moral injury fundamentally differ from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in terms of its classification and core mechanism?

List three distinct types of Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs) that can lead to moral injury.

Describe two symptoms that are considered more specific to moral injury, beyond the general overlap with PTSD symptoms.

Explain the concept of "anhedonia" as a symptom of moral injury, differentiating between its social and physical forms.

What role do "betrayal" experiences play in the development of moral injury, according to the provided texts?

Briefly explain the relationship between "morals," "ethics," and "values" in the context of moral injury.

Why is an accepting and non-judgmental stance important for therapists treating moral injury?

Besides military veterans, name at least two other professional groups explicitly mentioned as being at high risk for moral injury.

How can "making meaning" out of a PMIE contribute to mitigating the negative impacts of moral injury?

What is "moral resilience," and how does it relate to overcoming the adversity associated with a PMIE?

Quiz Answer Key

Moral injury is considered a "dimensional problem" rather than a mental disorder, unlike PTSD which is a diagnosed mental disorder. Its core mechanism involves the transgression of deeply held moral beliefs and expectations, which is not a necessary component for a PTSD diagnosis.

Three types of PMIEs are self-oriented moral transgressions (doing or failing to do something against one's values), other-oriented moral transgressions (witnessing someone else commit a transgression), and betrayal (a transgression committed by a trusted person or group).

Symptoms more specific to moral injury include ongoing feelings of grief, guilt, and shame, particularly shame that generalizes to one's entire self ("I am bad"). Another specific symptom is social alienation, characterized by withdrawal, isolation, and rejecting loved ones.

Anhedonia, in the context of moral injury, is the inability to feel pleasure. Social anhedonia means a lack of desire to spend time with friends and family, while physical anhedonia refers to not finding pleasure in physical sensations like a hug or sex.

Betrayal plays a significant role in moral injury when it involves a transgression by someone in a position of legitimate authority or a trusted person/group in a high-stakes situation. This can lead to feelings of anger, loss of trust, and contribute to the overall psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual harm.

Morals are universal laws setting the foundation for behavior. Ethics are context-driven codes of behavior based on morals. Values are concepts based on morals and ethics that individuals freely choose and internalize, guiding their beliefs and actions. Moral injury occurs when these deeply held morals, ethics, or core values are violated.

An accepting and non-judgmental stance is crucial for therapists because patients with moral injury often carry deep feelings of guilt and shame, making them hesitant to share their experiences. They may fear judgment from the therapist, which could negatively impact their engagement and compliance with treatment.

Besides military veterans, Public Safety Personnel (PSP) such as police officers, firefighters, and paramedics, as well as healthcare workers, are explicitly mentioned as professional groups at high risk for moral injury due to the moral complexities and high-stakes decisions inherent in their duties.

"Making meaning" out of a PMIE involves actively acknowledging the event, identifying the specific transgression of values, addressing the symptoms, and then restoring or revising one's morals, ethics, or values. This process allows individuals to contextualize their actions and integrate them into a larger, more coherent narrative, thereby mitigating negative impacts.

Moral resilience describes an individual's ability to adapt, resolve, and overcome the adversity associated with a PMIE, ultimately regaining a sense of identity, purpose, and wholeness. It involves accepting personal limitations, identifying one's moral compass, and constructively addressing the systemic or personal factors that led to the PMIE.

3. Essay Questions

Compare and contrast the diagnostic criteria, hallmark symptoms, and underlying mechanisms of Moral Injury and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as presented in the source materials. Discuss the implications of considering them distinct but potentially overlapping conditions.

Analyze the multifaceted impact of moral injury across the occupational, psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual domains. Provide specific examples from the text for each domain to illustrate the breadth of its effects on an individual's life.

Discuss the framework of "morals, ethics, and values" (MEV) as described in the sources. Explain how transgressions within this framework contribute to the development of moral injury and how an individual's core values relate to their sense of self and identity in this context.

Evaluate the various approaches to treating moral injury, including both trauma-focused PTSD treatments and those specifically under investigation for MI. What challenges do therapists face when treating patients with moral injury, and what considerations are paramount for effective intervention?

Beyond military combat, explain how moral injury can manifest in different professional contexts, such as Public Safety Personnel (PSP) or healthcare workers. Discuss the factors unique to these roles that might predispose individuals to PMIEs and how organizational support or lack thereof might influence outcomes.

4. Glossary of Key Terms

Anhedonia: The inability to feel pleasure. This can manifest as social anhedonia (lack of desire to spend time with friends/family) or physical anhedonia (inability to find pleasure in physical sensations).

Betrayal: A type of Potentially Morally Injurious Event (PMIE) involving a transgression of morals, ethics, or values committed by a trusted person or group, especially those in positions of legitimate authority, in a high-stakes situation.

Behaviours: The activities (external and internal) that individuals engage in response to external or internal stimuli, often driven by values derived from ethics and morals.

Dimensional Problem: A classification for moral injury, suggesting it exists on a spectrum of severity or experience, rather than being a categorical mental disorder with fixed diagnostic criteria.

Ethics: Specific, context-driven codes of behavior that are based upon morals. They are the operationalization of moral precepts for a particular group or profession.

Moral Growth: The positive psychological change experienced by an individual due to struggling with morally challenging life circumstances or a moral injury, leading to personal development.

Moral Injury (MI): A psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual harm or impairment that results from experiencing a violation of deeply held moral beliefs, expectations, ethics, or personal values.

Moral Resilience: The ability to adapt, resolve, and overcome the adversity associated with exposure to a Potentially Morally Injurious Event (PMIE), ultimately regaining a sense of identity, purpose, and wholeness.

Morals: Universal laws or principles that establish the fundamental foundation for how societies, organizations, professions, and individuals are expected to behave, regardless of personal characteristics.

Moral Strength: An individual's capacity, motivation, and willingness to take moral action, especially by acting in ways that are personally congruent even during exposure to a Potentially Morally Injurious Event (PMIE).

MI Symptoms: The pain, suffering, struggle, distress, or impairment a person experiences due to a moral injury, encompassing various domains of life, health, and well-being.

Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs): Events or exposures that involve actions, inactions (omission), or betrayals that transgress a person’s deeply held moral beliefs, ethics, or values.

Potentially Psychologically Traumatic Event (PPTE): A stressful event involving actual, perceived, or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, which may cause psychological trauma consistent with mental health conditions like PTSD.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): A recognized mental disorder that can result from exposure to a life-threatening or harmful traumatic event, characterized by symptoms such as re-experiencing the event, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal.

Public Safety Personnel (PSP): A broad term encompassing diverse individuals who ensure public safety and security, including military members, veterans, police officers, firefighters, paramedics, correctional officers, and 911 dispatchers.

Self-Forgiveness: The process by which individuals come to terms with and accept behaviors that violated their principles or moral code, moving past guilt and shame. Difficulty with self-forgiveness is a hallmark of moral injury.

Shame: A core hallmark reaction to moral injury where the belief about a morally injurious event generalizes to the whole self (e.g., "I am bad because of what I did"). Distinct from guilt, which focuses on the act itself ("I did something bad").

Social Alienation: A symptom of moral injury characterized by withdrawal, isolation, rejection of loved ones, and distancing oneself from personal feelings.

Trauma-Focused PTSD Treatment: Therapeutic approaches like Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) designed to address trauma-related symptoms, which may also reduce guilt and shame, but might not fully address moral injury specific concerns.

Values: Concepts based on morals and ethics that an individual has freely chosen and internalized, which guide their beliefs and actions and reflect their core sense of self.

Virtues: Core values that consistently guide behaviors across situations, become self-reinforcing, and eventually form a part of a person's character and identity.

5. Timeline of Main Events

Ancient Greece (c. 384-322 BCE)

Aristotle's contributions to ethics: His work, particularly "Nicomachean Ethics," lays a foundational philosophical understanding of virtues and moral behavior, influencing later concepts of morality.

Medieval Period (c. 1225-1274 CE)

Thomas Aquinas's theological and philosophical contributions: His "Summa Theologica" further develops the concept of universal moral laws rooted in reason, aligning with the idea of objective morality.

18th Century CE (c. 1724-1804 CE)

Immanuel Kant's philosophical work on morality: Kant's emphasis on universal moral laws based on reason, aligns with the understanding of "morals" as universal principles.

Mid-1980s

Development and validation of the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI): E. S. Kubany and colleagues published this measure in 1996, indicating an earlier focus on specific trauma-related emotions like guilt.

1995

Publication of "Trauma & transformation: growing in the aftermath of suffering" by Richard G. Tedeschi: This work contributes to the understanding of "posttraumatic growth," a concept related to positive outcomes from traumatic events.

1996

Publication of "Development and validation of the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory" by Kubany, E. S., et al.: This marks a formal step in assessing specific components related to moral distress.

2001

Publication of "Being Good" by Simon Blackburn: This philosophical work likely contributes to ongoing discussions about the nature of goodness and morality.

2003

Publication of "Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived" (edited by Keyes and Haidt): This book includes Jonathan Haidt's concept of "Elevation and the positive psychology of morality," contributing to the understanding of positive moral emotions.

2007

Publication of "Sophie’s world: A novel about the history of philosophy" by Jostein Gaarder: This work makes philosophical concepts, including those related to ethics, accessible to a wider audience.

2008

Publication of "Why can’t we be good?" by Jacob Needleman: This work explores the human struggle with moral behavior.

2009

Initial conceptualization of Moral Injury (MI) in military settings: B. T. Litz, N. Stein, E. Delaney, L. Lebowitz, W. P. Nash, C. Silva, and S. Maguen publish "Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy," marking a foundational definition and model for MI in veterans.

Publication of "Buddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love and Wisdom": This book by Rick Hanson provides insights into how the brain processes memories and how trauma therapy can work by shifting emotional shadings.

2010

Publication of "Achilles in Vietnam: combat trauma and the undoing of character" by Jonathan Shay: This book highlights the profound impact of combat trauma on a person's character, aligning with the concept of moral injury.

2012

Publication of "Killing in combat may be independently associated with suicidal ideation" by S. Maguen, et al.: This study highlights a significant consequence of combat experiences, further emphasizing the need to understand specific traumas like moral injury.

Development and validation of the Trauma Related Shame Inventory (TRSI): T. Øktedalen and colleagues published this measure in 2014, indicating a growing focus on shame as a distinct trauma-related emotion.

2014

Jonathan Shay defines Moral Injury as "A betrayal of what’s right by someone who holds legitimate authority": This provides an additional perspective on the nature of MI, particularly regarding betrayal.

Publication of "The Trauma Related Shame Inventory: Measuring trauma-related shame among patients with PTSD" by T. Øktedalen, et al.: This provides a specific tool for assessing shame related to trauma.

2015

J. D. Jinkerson defines MI as "A particular trauma syndrome including psychological, existential, behavioral, and interpersonal issues": This expands the understanding of MI beyond just psychological distress.

Initial psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Questionnaire--Military Version (MIQ-MV) by J. M. Currier, et al.: This marks the development of specific assessment tools for moral injury in military populations.

Publication of "Moral Injury, Meaning Making, and Mental Health in Returning Veterans" by Currier, J. M., et al.: This study explores the role of meaning-making in mitigating the negative impacts of MI.

2017

Publication of "The American Journal of Nursing" article "Cultivating Moral Resilience" by Cynda H. Rushton: This article introduces and defines the concept of "moral resilience."

Development and evaluation of the Expressions of Moral Injury Scale--Military Version by J. M. Currier, et al.: Another specific assessment tool for MI.

2018

Publication of "Moral injury in UK armed forces veterans: a qualitative study" by V. Williamson, et al.: This study explores MI experiences among UK veterans.

Publication of "Adaptive Disclosure: A New Treatment for Military Trauma, Loss, and Moral Injury" by B. T. Litz, L. Lebowitz, M. J. Gray, and W. P. Nash: This introduces a specific therapeutic intervention for MI.

2019

Publication of "Moral Injury: An Integrative Review" by B. J. Griffin, et al.: This comprehensive review summarizes the understanding of MI to date.

Development of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy adapted for moral injury (ACT-MI): This 12-session group treatment is under investigation.

Development of Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (TrIGR): This 6-session individual therapy targets guilt and shame related to trauma.

2020

Publication of "The role of moral injury in PTSD among law enforcement officers" by K. Papazoglou, et al.: This brief report extends the concept of moral injury to law enforcement personnel.

Publication of "Moral injury and social well-being: A growth curve analysis" by R. P. Chesnut, et al.: This study examines the social impact of moral injury.

Publication of "COVID-19 exacerbates violence against health workers" by S. Devi and "Policing in pandemics" by J. Laufs and Z. Waseem: These works highlight situations where moral injury can occur in healthcare and public safety during a pandemic.

2021

Publication of "Moral injury and suicidal behavior among US combat Veterans" by B. Nichter, et al.: This study reinforces the link between MI and suicidal ideation/behavior.

Publication of "Meat in a Seat: A Grounded Theory Study Exploring Moral Injury in Canadian Public Safety Communicators, Firefighters, and Paramedics" by L. Smith-MacDonald, et al.: This qualitative study further explores MI in public safety personnel.

2022

Validation of the Moral Injury Outcomes Scale (MIOS) with Veterans and acute care nurses by B. T. Litz, et al. and H. Tao, et al.: This provides a validated tool for assessing MI outcomes.

2023

Publication of "Moral Injury and the Distress Scale (MIDS): Psychometric evaluation and initial validation in three high-risk populations" by S. B. Norman, et al.: This comprehensive measure links PMIEs to distress and symptoms across various populations.

Publication of "Moral injury and peri- and post-military suicide attempts among post-9/11 Veterans" by S. Maguen, et al.: This study further connects moral injury to suicide attempts.

Publication of "Moral injury and substance use disorders among US combat veterans" by S. Maguen, et al.: This study highlights the association between MI and substance abuse.

May 14, 2025 (Projected)

"How a VA Remand Can Affect Your Disability Claim" blog post by Cuddigan Law.

April 3, 2025 (Projected)

"You May Qualify for a Higher VA Rating for Tinnitus" blog post by Cuddigan Law.

February 25, 2025 (Projected)

"Why Your DD214 is Essential for Your VA Disability Claim" blog post by Cuddigan Law.

June 1, 2025 (Projected)

"Free App Matches Veterans with Personalized List of Benefits" library post by Cuddigan Law.

April 20, 2025 (Projected)

"Supreme Court Rules Against Veterans" library post by Cuddigan Law.

March 19, 2025 (Projected)

"Meet Stephani Bennett" library post by Cuddigan Law.

Cast of Characters

Philosophers & Theologians (Historical Figures)

Aristotle: An ancient Greek philosopher whose ethical writings, particularly "Nicomachean Ethics," provide a foundation for understanding virtues and moral behavior, influencing later discussions on morality.

Thomas Aquinas: A medieval Catholic theologian and philosopher who contributed significantly to the understanding of universal moral laws, grounding them in reason and theological principles.

Immanuel Kant: An 18th-century German philosopher known for his ethical theory, which emphasizes universal moral duties and the categorical imperative, contributing to the concept of universal moral laws.

Simon Blackburn: A contemporary British philosopher who has written on ethics, including "Being Good," contributing to modern philosophical discourse on morality.

Jostein Gaarder: A Norwegian author known for "Sophie's World," a philosophical novel that introduces philosophical concepts, including ethics, to a broad audience.

Jacob Needleman: An American philosopher and author whose work, such as "Why Can't We Be Good?", explores the challenges of moral living.

Researchers & Clinicians (Key Contributors to Moral Injury Research)

B. T. Litz: A prominent researcher in the field of moral injury. He is a co-author of the foundational 2009 paper that proposed a preliminary model and intervention strategy for moral injury in war veterans. He is also involved in the development of the Moral Injury Outcomes Scale (MIOS) and Adaptive Disclosure treatment.

S. Maguen: A key researcher in moral injury, co-authoring several significant studies linking moral injury to suicidal ideation and substance use disorders among veterans. She is also involved in validating the Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS).

Jonathan Shay: A psychiatrist and author whose book "Achilles in Vietnam" profoundly influenced the understanding of combat trauma and its impact on character, pre-dating and contributing to the concept of moral injury. He also offers a specific definition of moral injury as a "betrayal of what's right."

J. M. Currier: A researcher involved in the development and evaluation of several moral injury assessment tools, including the Moral Injury Questionnaire--Military Version and the Expressions of Moral Injury Scale--Military Version. He also studies the role of meaning-making in moral injury.

S. B. Norman: A researcher actively involved in the psychometric evaluation and validation of moral injury assessment tools like the Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS) and studies the prevalence of moral injury in veterans.

Richard G. Tedeschi: A psychologist known for his work on posttraumatic growth, a concept that explores positive psychological changes following traumatic experiences.

Rick Hanson: An author of "Buddha's Brain," which applies neuroscience to psychological well-being, including how the brain processes memories and how trauma therapy can lead to neural changes.

John Briere: A researcher from the Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Southern California, who synthesizes Buddhist and Western approaches to trauma, contributing to the understanding of trauma treatment.

Cynda H. Rushton: The author of "Cultivating Moral Resilience," an article in "The American Journal of Nursing" that defines and explores the concept of moral resilience.

K. Papazoglou: A researcher who co-authored a brief report on the role of moral injury in PTSD among law enforcement officers, expanding the applicability of MI beyond military contexts.

L. Smith-MacDonald: A researcher involved in qualitative studies exploring moral injury in Canadian public safety communicators, firefighters, and paramedics.

Organizations & Entities

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs): A US government agency that recognizes PTSD as a mental disorder and moral injury as a "dimensional problem," providing information, resources, and treatment guidelines for veterans. They also oversee various mental health and disability benefits programs.

Cuddigan Law: A law firm specializing in SSA and VA disability benefits, offering legal support and advice to veterans seeking disability claims, including those related to PTSD and moral injury.

PTSD Consultation Program: An expert guidance program offered by the National Center for PTSD, specifically designed to assist in treating Veterans with PTSD.

Public Safety Personnel (PSP): A broad category of individuals who ensure public safety, including border services officers, Canadian Armed forces members and Veterans, correctional services and parole officers, firefighters, Indigenous emergency managers, operational intelligence personnel, paramedics, police officers, public safety communicators, and search and rescue personnel. They are increasingly recognized as experiencing moral injury.

6. FAQ

What is Moral Injury (MI)?

Moral Injury (MI) is a psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual harm that occurs when an individual experiences or witnesses events that deeply violate their moral beliefs, ethics, or personal values. These events can involve an "act of commission" (doing something that goes against their beliefs), an "act of omission" (failing to do something in line with their beliefs), or a "betrayal" from those in authority or trusted peers. The distress from MI arises from the transgression of what the individual perceives as "right" or "just." While often associated with military combat, MI can affect anyone in high-stakes situations, such as public safety personnel (e.g., firefighters, police, paramedics) who are routinely exposed to morally challenging circumstances.

How does Moral Injury differ from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

While both Moral Injury and PTSD can stem from traumatic events and share overlapping symptoms like anger, depression, insomnia, and substance abuse, they are distinct conditions. PTSD is recognized as a mental disorder primarily associated with fear-based reactions to actual or threatened death, injury, or sexual violence. Moral Injury, however, is considered a "dimensional problem" and focuses on the psychological aftermath of events that transgress deeply held moral beliefs. Key differences include:

Mechanism of Injury: PTSD results from a perceived threat to physical integrity; MI results from a transgression of moral, ethical, or deeply held personal values.

Core Emotional Reactions: While guilt and shame can be present in both, they are hallmark features of MI. MI also uniquely involves feelings of disgust and anger related to moral transgressions or betrayal. PTSD also includes hyperarousal which is not central to MI.

Diagnosis: PTSD is a diagnosable mental disorder. MI is not currently a formal mental disorder within diagnostic systems like the DSM-5-TR or ICD-10, though its symptoms may overlap with various mental health conditions.

Treatment Focus: While some trauma-focused PTSD treatments may help with elements of MI, specific MI treatments often address concerns like self-forgiveness, restoring values, and making meaning out of the event.

It's important to note that an individual can experience neither, either, or both PTSD and MI simultaneously. Having MI in addition to PTSD is often associated with more severe PTSD and depression symptoms and a higher likelihood of suicidal ideation and behaviors.

What are the key symptoms of Moral Injury?

While some symptoms of MI overlap with PTSD, such as anger, depression, insomnia, nightmares, anxiety, and substance abuse, there are several symptoms more specific to moral injury, impacting occupational, psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual domains:

Emotional Distress: Profound feelings of grief, guilt, and shame. Guilt involves distress over actions ("I did something bad"), while shame generalizes to self-identity ("I am bad because of what I did"). Disgust may arise from memories of perpetration, and anger from feelings of loss or betrayal.

Social Alienation: Withdrawal, isolation, and rejection of loved ones, friends, and social connections. This can lead to feeling disconnected even when in company.

Trust and Forgiveness Issues: Difficulty trusting oneself, friends, family, and the world. A breakdown in self-forgiveness is common, and some individuals may not believe they deserve to feel better, leading to self-sabotaging behaviors.

Anhedonia: The inability to feel pleasure, affecting social interactions (social anhedonia) or physical sensations (physical anhedonia).

Cognitive and Existential Challenges: Intrusive thoughts or imagery, cognitive rigidity (e.g., "all-or-nothing" thinking), questioning pre-existing spiritual/religious beliefs, beliefs about humanity and the world, and the meaning of life. This can manifest as a loss of faith, fractured world-beliefs, and a questioned sense of self and identity.

Behavioral: Self-destructive behaviors, intense self-criticism, and difficulties in regulating emotions which can motivate distress-reducing behaviors such as substance abuse, dissociation, self-injury, suicidality, and aggression.

These symptoms can vary widely in experience and severity.

What are "Potentially Morally Injurious Events" (PMIEs)?

Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs) are the specific experiences that can lead to moral injury. They are defined as exposures to actions, inactions, or events that violate an individual's moral, ethical, or deeply held personal values. PMIEs can be categorized in a few ways:

Acts of Commission: Purposeful behaviors undertaken by a person that go against their moral code (e.g., participating in killing others in combat).

Acts of Omission: Failing to do something in line with one's moral beliefs (e.g., not preventing other soldiers from performing immoral acts).

Betrayal: Transgressions committed by a trusted person or group of people, especially those in positions of authority (e.g., leaders failing to provide sufficient resources, or a loved one committing an assault).

These events can be acute (single event), chronic, or cumulative, and while often discussed in military contexts, they can occur in any profession or situation where individuals are faced with moral dilemmas or violations.

Who is most susceptible to Moral Injury?

While traditionally associated with military personnel and veterans due to combat exposure, moral injury can affect a wide range of individuals, particularly those in professions where they are regularly exposed to high-stakes, morally challenging situations. This includes:

Public Safety Personnel (PSP): Border services officers, Canadian Armed Forces members and Veterans, correctional services and parole officers, firefighters, Indigenous emergency managers, operational intelligence personnel, paramedics, police officers, public safety communicators (e.g., 911 dispatchers), and search and rescue personnel. These individuals often face rapid decision-making in complex crises involving conflicting responsibilities, uncertainty, and ambiguity.

Healthcare Professionals: Nurses and other healthcare workers can experience moral injury when they are unable to provide adequate care due to systemic failures or resource limitations, or witness traumatic events that violate their professional ethics.

Anyone experiencing betrayal or moral transgression: The concept extends beyond these specific professions to anyone who experiences a violation of their deeply held moral beliefs, whether through their own actions, the actions of others, or perceived betrayals. Individual factors like genetics, adverse childhood experiences, personality, and existing spiritual or religious beliefs can also influence how a person is impacted by a PMIE.

How are morals, ethics, and values related to Moral Injury?

Moral injury arises specifically from the violation of an individual's morals, ethics, and values, which are distinct yet interconnected concepts that guide behavior:

Morals: These are universal laws that form the foundation for how societies, organizations, professions, and individuals are expected to behave (e.g., the inherent value of life). They are considered external and universal.

Ethics: These are specific, context-driven codes of behavior that are based upon morals. Ethical codes operationalize moral rules for particular groups or professions (e.g., a police officer's promise to engage with trust, or a paramedic's commitment to preserve human life).

Values: These are internal concepts derived from morals and ethics that an individual freely chooses and prioritizes, guiding their beliefs and actions. Values reflect who a person is and are demonstrated through their behaviors (e.g., authenticity, compassion, justice, loyalty). Core values are fundamental to a person's sense of self and identity.

When an individual's actions, inactions, or experiences transgress these deeply held morals, ethics, or core values, it can lead to moral injury, damaging their character, identity, and deepest sense of self. They may feel as though they are betraying who they are, leading to feelings of being "broken" or "not who they used to be."

How is Moral Injury assessed?

Assessing moral injury requires a specific approach to accurately identify exposure to Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs) and the symptoms directly linked to them. It's crucial to differentiate these from general trauma symptoms. Key assessment tools and approaches include:

Identification of PMIEs: Clinicians need to inquire about specific events where the individual perpetrated, failed to prevent, witnessed, or experienced betrayal related to deeply held moral beliefs. It's common for patients to initially withhold their "worst" event due to guilt or shame, so therapists must create a non-judgmental and accepting environment.

Validated Measures: Psychometric studies have led to the development of specific scales for assessing moral injury:

Moral Injury Outcomes Scale (MIOS): Validated with veterans and nurses, it has a two-factor structure capturing shame and trust.

Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS): A comprehensive measure linking PMIEs to subjective distress and moral injury symptoms, validated across veterans, healthcare workers, and first responders. It provides a unidimensional sum score indicating severity.

Core Feature Measures: Tools like the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory and the Trauma Related Shame Inventory can specifically measure feelings and beliefs related to guilt and shame in the context of traumatic events, and are validated for non-military samples.

Clinical Interviewing: Therapists are encouraged to be alert to self-sabotaging behaviors or beliefs that the patient doesn't deserve to feel better, as these can be clues to an undisclosed moral injury.

The goal is to understand the specific mechanism of injury—the violation of morals, ethics, or values—to guide effective treatment.

What are the treatment approaches for Moral Injury?

Treatment for moral injury often involves specialized therapies that address the unique psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual aftermath of moral transgressions. While some trauma-focused PTSD treatments (like Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy) can help reduce trauma-related guilt and shame, additional or specific interventions may be necessary, especially if the core moral injury issues remain unresolved.

Current and developing treatment approaches include:

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) adapted for moral injury: Focuses on helping patients live in accordance with their values, even in the presence of painful experiences.

Adaptive Disclosure: An individual therapy that processes moral injury through imaginary dialogue with a compassionate moral authority, blame apportionment, amends-making, and sometimes self-compassion and mindfulness.

The Impact of Killing intervention: A phased individual therapy, often delivered after PTSD treatment, that helps patients explore the functional impact of unforgiveness, develop a forgiveness plan (e.g., letter writing), and create an amends plan to honor violated values.

Moral Injury Group: A group intervention co-delivered by a chaplain and psychologist, which may include ceremonies where participants share testimonies.

Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (TrIGR): A short-term individual therapy that helps patients identify and evaluate beliefs contributing to guilt and shame, clarify values, and plan to live in line with those values.

Building Spiritual Strength: An 8-session group therapy led by a chaplain, addressing relationships with a Higher Power and challenges with forgiveness.

Key aspects of successful treatment also include:

Therapist Stance: Conveying an accepting, non-judgmental, and empathic stance, while also being aware of one's own presumptions about morals and values.

Self-Reflection and Psychoeducation: Encouraging self-awareness of personal and professional morals, ethics, and values, and educating individuals about PMIEs and MI to develop proactive coping plans.

Distinguishing Self from Actions: Helping individuals separate "who one is" from "what one has done or has not done" to prevent internalizing negative beliefs.

Meaning-Making: Acknowledging the PMIE, understanding the transgression, restoring or revising values, and integrating the experience into a larger narrative through practices like expressive writing or spiritual practices.

Holistic Approach: Recognizing the biopsychosociospiritual model of MI, potentially involving religious or spiritual guidance from chaplains alongside mental health professionals, regardless of the patient's specific religion.

7. Table of Contents

Introduction and Welcome .................................................... 0:00 Opening scenario and podcast introduction, setting the stage for understanding moral injury as distinct from traditional trauma concepts.

Chapter 1: Defining Moral Injury ............................................ 2:15 Core definition of moral injury as psychological wound from moral transgressions, distinguishing it from emotional distress and establishing its unique characteristics.

Chapter 2: Beyond the Military Context ..................................... 4:30 Expansion from traditional military applications to public safety personnel, healthcare workers, and broader professional contexts where moral conflicts arise.

Chapter 3: PTSD vs. Moral Injury ........................................... 6:45 Critical distinctions between fear-based PTSD and conscience-based moral injury, including overlapping symptoms and diagnostic considerations.

Chapter 4: The Spectrum of Experience ...................................... 9:20 Understanding moral injury as dimensional rather than binary, exploring varying degrees of impact and individual responses to morally injurious events.

Chapter 5: Emotional Hallmarks ............................................ 11:40 Specific symptoms unique to moral injury: profound grief, guilt, shame, social alienation, loss of trust, anhedonia, and spiritual crisis.

Chapter 6: Guilt vs. Shame Framework ...................................... 14:10 Deep dive into the distinction between "I did something bad" (guilt) versus "I am bad" (shame) and implications for healing.

Chapter 7: The MEV Framework .............................................. 16:25 Exploration of Morals, Ethics, and Values as foundational elements that become damaged in moral injury, affecting core identity and character.

Chapter 8: Categories of Moral Transgressions ............................. 18:50 Three types of potentially morally injurious events: self-oriented, other-oriented, and betrayal-based transgressions with concrete examples.

Chapter 9: Factors Influencing Response ................................... 21:35 Five key elements affecting individual responses: exposure intensity, personal role, perceived agency, MEV framework, and repair possibility.

Chapter 10: Public Safety Personnel Examples .............................. 24:20 Specific moral injury scenarios common in police, fire, EMS, and healthcare settings, including resource limitations and public hostility.

Chapter 11: The Pain Paradox .............................................. 27:45 How attempts to avoid emotional pain through suppression or numbing often intensify and prolong moral injury symptoms.

Chapter 12: Ripple Effects Across Life Domains ........................... 30:30 Comprehensive impact analysis: occupational, psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual consequences of untreated moral injury.

Chapter 13: Diversity and Equity Considerations ........................... 34:15 How gender, ethnicity, and systemic discrimination influence moral injury experience and recovery, including specific risks for marginalized groups.

Chapter 14: Moral Resilience and Growth ................................... 37:00 Positive outcomes and post-traumatic growth potential, leveraging pro-social characteristics for healing and renewed purpose.

Chapter 15: Organizational Prevention Strategies .......................... 39:45 Creating psychologically safe workplaces, moral resilience training, leadership responsibilities, and team cohesion building.

Chapter 16: Professional Treatment Approaches ............................. 43:20 Traditional trauma therapies versus specialized moral injury interventions, including ACT, TRIG-ERR, and spiritually-informed treatments.

Chapter 17: Informal Support Systems ...................................... 47:10 Role of peer support, family networks, and community connections in healing, including psychoeducation for support persons.

Chapter 18: Individual Self-Care Practices ................................ 50:25 Personal strategies for healing: self-awareness, psychoeducation, distinguishing identity from actions, spiritual practices, and expressive arts.

Chapter 19: Collective Responsibility ..................................... 53:40 Community implications and transformative potential of supporting those with moral injury across various professions and contexts.

Conclusion and Reflection ................................................. 56:15 Summary of key concepts and call to action for collective understanding and support of moral injury survivors.

Closing Credits and Resources ............................................. 58:30 Podcast information, recurring narrative themes, and additional resources for continued exploration.

8. Index

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): 46:20

Adaptive Complexity: 58:45

Adaptive Disclosure: 46:35

Agency, Perceived: 21:50

Alienation, Social: 15:20

Anhedonia: 16:05

Anxiety: 9:35

Avoidance: 28:10, 51:40

Beliefs, Core: 16:50

Betrayal: 19:40, 25:15

Boundary Dissolution: 58:30

Building Spiritual Strength: 47:00

Burnout: 33:20

Character Damage: 18:30

Chaplain-Led Interventions: 46:55

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT): 45:30

Commission, Acts of: 20:25

Compassion Fatigue: 33:25

COVID-19 Pandemic: 26:40

Crisis, Spiritual: 16:50

Decompression Time: 42:50

Depression: 9:40

Dimensional Problem: 8:45

Discrimination, Systemic: 35:10

Disgust: 32:50

Embodied Knowledge: 58:35

Ethics: 17:05

Existential Doubt: 33:45

Expressive Arts: 52:10

Fear-Based Trauma: 7:20

Firefighter Examples: 19:10, 24:35

Forgiveness, Self: 15:45, 33:40

Gender Inequities: 36:20

Gratitude Practice: 52:35

Grief, Profound: 12:20

Group Therapy: 46:50

Guilt: 12:25, 14:15

Healthcare Workers: 5:15, 25:05

Helplessness: 32:55

Hope, Cultivating: 52:30

Identity Damage: 18:35

Impact of Killing Treatment: 46:45

Insomnia: 9:30

Intergenerational Trauma: 35:25

Interpersonal Risk-Taking: 41:15

Isolation: 15:25, 33:15

Journaling: 52:05

Leadership Responsibilities: 42:15

Meaning, Loss of: 17:00

Meditation: 52:45

MEV Framework: 16:30

Military Context: 4:45

Mindfulness: 52:40

Moral Injury Group: 46:50

Moral Resilience: 37:15, 40:15

Moral Resilience Training: 41:45

Moral Transgressions: 19:00

Morals: 16:55

Nature, Time in: 52:50

Nightmares: 9:25

Nonjudgmental Stance: 47:30

Numbing: 28:05

Omission, Acts of: 20:30

Organizational Betrayal: 20:05

Other-Oriented Transgressions: 19:20

Pain Paradox: 27:50

Paramedic Examples: 0:45, 20:10, 24:50

Peer Support: 49:25

Police Examples: 19:30, 24:25

Post-Traumatic Growth: 38:15

Prayer: 52:40

Pro-Social Characteristics: 37:45

Prolonged Exposure (PE): 45:25

Psychoeducation: 49:55, 51:20

PTSD Distinction: 6:50, 8:20

Public Safety Personnel (PSP): 5:25, 24:20

Quantum-like Uncertainty: 58:40

Racism, Systemic: 35:15

Repair Possibility: 22:25

Resource Limitations: 24:40

Role Models: 41:05

Rotation, Staff: 42:45

Self-Awareness: 51:15

Self-Blame: 10:15

Self-Criticism: 33:30

Self-Forgiveness: 15:45

Self-Oriented Transgressions: 19:05

Self-Reflection: 52:00

Self-Sabotaging Behaviors: 15:55

Sexual Misconduct: 36:25

Shame: 12:30, 14:20

Spirituality Impact: 16:45

Substance Abuse: 9:45

Suicidal Ideation: 33:35

Team Cohesion: 43:05

Transgression, Moral: 8:05

Trauma-Informed Guilt Reduction (TRIG-ERR): 46:40

Trust, Loss of: 15:35

Values: 17:15

Veterans: 4:40

Withdrawal: 15:30

9. Post-Episode Fact Check

VERIFIED CLAIMS:

Moral Injury Definition and Distinction from PTSD: The episode correctly defines moral injury as distinct from PTSD, with moral injury occurring when deeply held morals or values are violated, and research confirming it as "a separate aspect of trauma exposure, distinct from posttraumatic stress disorder" VaPsychiatryonline.

Dimensional vs. Binary Nature: The episode accurately describes moral injury as "a dimensional problem" rather than a simple diagnosis Moral Injury and PTSD: Often Co-Occurring Yet Mechanistically Different | The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, which aligns with current research.

Prevalence in High-Risk Populations: Recent research confirms high exposure rates: "49.3% of combat veterans, 50.8% of healthcare workers, and 41.6% of first responders endorsed exposure to a PMIE [potentially morally injurious event]" Prevalence of Moral Injury in Nationally Representative Samples of Combat Veterans, Healthcare Workers, and First Responders | Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Impact on Healthcare Workers and First Responders: Research confirms increased risk for moral injury among "uniformed service members" and "frontline health workers," and identifies it as "an occupational hazard" during COVID-19 NihFrontiers.

Symptom Severity: The episode's claim about increased severity is supported: "when someone has moral injury in addition to PTSD, the PTSD symptoms may be more severe" with increased depression and suicidal ideation Moral Injury and PTSD - PTSD: National Center for PTSD.

Treatment Development: The Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS) mentioned aligns with recent developments, having been "downloaded more than 28,000 times" since introduction The Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS): First of its Kind.

ACCURATE BUT EVOLVING CONCEPTS:

Treatment Approaches: The episode mentions several specialized treatments (ACT, TRIG-ERR, Building Spiritual Strength) which are legitimate approaches, though research notes that "definitions, ideas, and practices we're working with are both experimental and varied" What is Moral Injury - The Moral Injury Project – Syracuse University.

MEV Framework: While the episode's explanation of Morals, Ethics, and Values is conceptually sound, this specific framework terminology isn't universally standardized in the literature.

AREAS REQUIRING CAUTION:

Gender and Diversity Claims: While the episode mentions gender inequities and systemic discrimination impacts, the specific statistics and claims about betrayal-based moral injury in women weren't directly verified in the search results, though the concepts are plausible based on broader research patterns.

Specific Therapy Names: Some treatment modalities mentioned (like "trauma-informed guilt reduction therapy") may represent emerging or specialized approaches that aren't yet widely established in mainstream literature.

OVERALL ASSESSMENT:

The episode demonstrates strong factual accuracy on core concepts, definitions, and research findings. The fundamental understanding of moral injury, its distinction from PTSD, prevalence in high-risk populations, and treatment approaches aligns well with current academic and clinical literature. The episode's emphasis on the significance of the problem is supported by research showing "exposure to PMIEs is common and a sizable minority report clinically meaningful moral injury" Prevalence of Moral Injury in Nationally Representative Samples of Combat Veterans, Healthcare Workers, and First Responders - PubMed.

The content appears to be well-researched and current, drawing from legitimate academic and clinical sources. While some specific frameworks and treatment details may represent emerging concepts rather than fully established practices, the overall presentation is scientifically sound and clinically relevant.