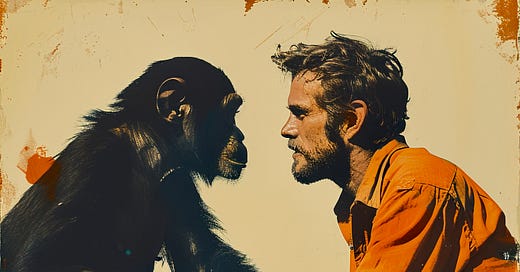

Human Exceptionalism: What Bonobos Know That We Don't

Revolutionary research from Johns Hopkins University is challenging everything we thought we knew about primate intelligence.

We've been telling ourselves a comforting lie about intelligence.

You know the lie I'm talking about – the story that puts humans at the pinnacle of evolution, looking down at all other species from our lofty perch of supposed cognitive superiority. It's the kind of self-congratulatory narrative that lets us sleep better at night while we reshape the planet in our image.

But here's the thing: that story is starting to fall apart.

New research from Johns Hopkins University, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, just delivered another blow to our species' ego. It turns out bonobos don't just communicate – they understand when others are missing information and actively work to fill those knowledge gaps.

Let that sink in for a moment.

These primates aren't just responding to stimuli or following trained behaviors. They're actually comprehending what other individuals do and don't know, and then acting on that understanding.

The experiment itself was deceptively simple: researchers set up a scenario where a human researcher either did or didn't know where a treat was hidden under one of several cups. The bonobos' response? They only pointed to the treat's location when the researcher hadn't seen where it was hidden.

When the researcher had witnessed the hiding process, the bonobos stayed quiet. They knew there was no need to share information that was already known.

This isn't just clever – it's a demonstration of what scientists call "theory of mind," the ability to understand that others have different knowledge, beliefs, and intentions than our own. It's something we've long claimed as uniquely human, along with language, complex social interaction, and teaching abilities.

Oops.

Here's where it gets really interesting: the bonobos weren't just pointing casually. They were insistent about it, sometimes repeatedly gesturing through their enclosure's mesh to make sure their message got across. It's almost as if they were thinking, "Come on, human, I'm trying to help you out here."

The implications are staggering.

First, it suggests that the capacity for understanding others' mental states isn't some recent evolutionary development that helped make humans special. Instead, it likely evolved millions of years ago in our common ancestors with other apes. This ability has been there all along – we just didn't want to see it.

Second, it forces us to confront our biases about intelligence itself. We've created this hierarchical model where human cognition sits at the top, and everything else is ranked below us in descending order of how closely it resembles our own thinking patterns.

But what if that's completely wrong?

What if intelligence isn't a linear progression but rather a vast landscape of different capabilities, each evolved to serve specific needs and circumstances? What if we're not at the top of a pyramid, but rather one point in a complex web of cognitive abilities?

The truth is, we've been measuring other species by human standards and then acting surprised when they don't measure up. It's like judging a fish by its ability to climb a tree, as the saying goes.

This research from Johns Hopkins isn't just about bonobos finding treats. It's about dismantling our assumptions about what constitutes intelligence and consciousness. It's about recognizing that other species might have rich mental lives that we've been too arrogant to acknowledge.

And here's the kicker: this isn't even the only evidence. Scientists have observed similar behaviors in wild chimpanzees, who vocalize warnings about threats only to group members who haven't already spotted the danger. They're not just mindlessly screaming about predators – they're taking into account what their companions do and don't know.

The researchers are already planning follow-up studies to investigate whether bonobos are actually trying to change others' mental states, not just their behavior. In other words, are they thinking about thinking?

The answer to that question might force us to completely reorganize our understanding of consciousness and intelligence in the natural world.

But there's something even more profound at stake here.

In an era where we're facing unprecedented environmental challenges and mass extinction, understanding that other species have complex cognitive abilities isn't just an academic exercise. It's a moral imperative.

If bonobos can understand what others don't know and actively work to share that information, what does that say about our responsibility to protect and preserve their habitats and communities? What does it say about our relationship with the countless other species whose cognitive abilities we might not yet understand?

The comfortable myth of human exceptionalism is crumbling, and it's about time. The real question isn't whether other species can think like us – it's whether we can expand our thinking enough to recognize and respect the diverse forms of intelligence that surround us.

Maybe then we'll start making better decisions about our role on this planet.

Because if there's one thing this research makes clear, it's that we're not as special as we thought we were. And that might be the most important lesson of all.

Reference: Bonobos realize when humans miss information and communicate accordingly

Primate Intelligence